- Home

- Charles Dickens

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 Page 2

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 Read online

Page 2

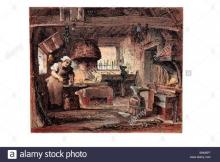

To have seen little Mrs. Peerybingle come back with her husband, tugging at the clothes–basket, and making the most strenuous exertions to do nothing at all (for he carried it), would have amused you almost as much as it amused him. It may have entertained the Cricket too, for anything I know; but, certainly, it now began to chirp again, vehemently.

‘Heyday!’ said John, in his slow way. ‘It’s merrier than ever, to–night, I think.’

‘And it’s sure to bring us good fortune, John! It always has done so. To have a Cricket on the Hearth, is the luckiest thing in all the world!’

John looked at her as if he had very nearly got the thought into his head, that she was his Cricket in chief, and he quite agreed with her. But, it was probably one of his narrow escapes, for he said nothing.

‘The first time I heard its cheerful little note, John, was on that night when you brought me home—when you brought me to my new home here; its little mistress. Nearly a year ago. You recollect, John?’

O yes. John remembered. I should think so!

‘Its chirp was such a welcome to me! It seemed so full of promise and encouragement. It seemed to say, you would be kind and gentle with me, and would not expect (I had a fear of that, John, then) to find an old head on the shoulders of your foolish little wife.’

John thoughtfully patted one of the shoulders, and then the head, as though he would have said No, no; he had had no such expectation; he had been quite content to take them as they were. And really he had reason. They were very comely.

‘It spoke the truth, John, when it seemed to say so; for you have ever been, I am sure, the best, the most considerate, the most affectionate of husbands to me. This has been a happy home, John; and I love the Cricket for its sake!’

‘Why so do I then,’ said the Carrier. ‘So do I, Dot.’

‘I love it for the many times I have heard it, and the many thoughts its harmless music has given me. Sometimes, in the twilight, when I have felt a little solitary and down–hearted, John—before baby was here to keep me company and make the house gay—when I have thought how lonely you would be if I should die; how lonely I should be if I could know that you had lost me, dear; its Chirp, Chirp, Chirp upon the hearth, has seemed to tell me of another little voice, so sweet, so very dear to me, before whose coming sound my trouble vanished like a dream. And when I used to fear—I did fear once, John, I was very young you know—that ours might prove to be an ill–assorted marriage, I being such a child, and you more like my guardian than my husband; and that you might not, however hard you tried, be able to learn to love me, as you hoped and prayed you might; its Chirp, Chirp, Chirp has cheered me up again, and filled me with new trust and confidence. I was thinking of these things to–night, dear, when I sat expecting you; and I love the Cricket for their sake!’

‘And so do I,’ repeated John. ‘But, Dot? I hope and pray that I might learn to love you? How you talk! I had learnt that, long before I brought you here, to be the Cricket’s little mistress, Dot!’

She laid her hand, an instant, on his arm, and looked up at him with an agitated face, as if she would have told him something. Next moment she was down upon her knees before the basket, speaking in a sprightly voice, and busy with the parcels.

‘There are not many of them to–night, John, but I saw some goods behind the cart, just now; and though they give more trouble, perhaps, still they pay as well; so we have no reason to grumble, have we? Besides, you have been delivering, I dare say, as you came along?’

‘Oh yes,’ John said. ‘A good many.’

‘Why what’s this round box? Heart alive, John, it’s a wedding–cake!’

‘Leave a woman alone to find out that,’ said John, admiringly. ‘Now a man would never have thought of it. Whereas, it’s my belief that if you was to pack a wedding–cake up in a tea–chest, or a turn–up bedstead, or a pickled salmon keg, or any unlikely thing, a woman would be sure to find it out directly. Yes; I called for it at the pastry–cook’s.’

‘And it weighs I don’t know what—whole hundredweights!’ cried Dot, making a great demonstration of trying to lift it.

‘Whose is it, John? Where is it going?’

‘Read the writing on the other side,’ said John.

‘Why, John! My Goodness, John!’

‘Ah! who’d have thought it!’ John returned.

‘You never mean to say,’ pursued Dot, sitting on the floor and shaking her head at him, ‘that it’s Gruff and Tackleton the toymaker!’

John nodded.

Mrs. Peerybingle nodded also, fifty times at least. Not in assent—in dumb and pitying amazement; screwing up her lips the while with all their little force (they were never made for screwing up; I am clear of that), and looking the good Carrier through and through, in her abstraction. Miss Slowboy, in the mean time, who had a mechanical power of reproducing scraps of current conversation for the delectation of the baby, with all the sense struck out of them, and all the nouns changed into the plural number, inquired aloud of that young creature, Was it Gruffs and Tackletons the toymakers then, and Would it call at Pastry–cooks for wedding–cakes, and Did its mothers know the boxes when its fathers brought them homes; and so on.

‘And that is really to come about!’ said Dot. ‘Why, she and I were girls at school together, John.’

He might have been thinking of her, or nearly thinking of her, perhaps, as she was in that same school time. He looked upon her with a thoughtful pleasure, but he made no answer.

‘And he’s as old! As unlike her!—Why, how many years older than you, is Gruff and Tackleton, John?’

‘How many more cups of tea shall I drink to–night at one sitting, than Gruff and Tackleton ever took in four, I wonder!’ replied John, good–humouredly, as he drew a chair to the round table, and began at the cold ham. ‘As to eating, I eat but little; but that little I enjoy, Dot.’

Even this, his usual sentiment at meal times, one of his innocent delusions (for his appetite was always obstinate, and flatly contradicted him), awoke no smile in the face of his little wife, who stood among the parcels, pushing the cake–box slowly from her with her foot, and never once looked, though her eyes were cast down too, upon the dainty shoe she generally was so mindful of. Absorbed in thought, she stood there, heedless alike of the tea and John (although he called to her, and rapped the table with his knife to startle her), until he rose and touched her on the arm; when she looked at him for a moment, and hurried to her place behind the teaboard, laughing at her negligence. But, not as she had laughed before. The manner and the music were quite changed.

The Cricket, too, had stopped. Somehow the room was not so cheerful as it had been. Nothing like it.

‘So, these are all the parcels, are they, John?’ she said, breaking a long silence, which the honest Carrier had devoted to the practical illustration of one part of his favourite sentiment—certainly enjoying what he ate, if it couldn’t be admitted that he ate but little. ‘So, these are all the parcels; are they, John?’

‘That’s all,’ said John. ‘Why—no—I—’ laying down his knife and fork, and taking a long breath. ‘I declare—I’ve clean forgotten the old gentleman!’

‘The old gentleman?’

‘In the cart,’ said John. ‘He was asleep, among the straw, the last time I saw him. I’ve very nearly remembered him, twice, since I came in; but he went out of my head again. Holloa! Yahip there! Rouse up! That’s my hearty!’

John said these latter words outside the door, whither he had hurried with the candle in his hand.

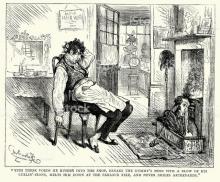

Miss Slowboy, conscious of some mysterious reference to The Old Gentleman, and connecting in her mystified imagination certain associations of a religious nature with the phrase, was so disturbed, that hastily rising from the low chair by the fire to seek protection near the skirts of her mistress, and coming into contact as she crossed the doorway with an ancient Stranger, she instinctively made a charge or butt at him with the only offensive instrument within her reach. This

instrument happening to be the baby, great commotion and alarm ensued, which the sagacity of Boxer rather tended to increase; for, that good dog, more thoughtful than its master, had, it seemed, been watching the old gentleman in his sleep, lest he should walk off with a few young poplar trees that were tied up behind the cart; and he still attended on him very closely, worrying his gaiters in fact, and making dead sets at the buttons.

‘You’re such an undeniable good sleeper, sir,’ said John, when tranquillity was restored; in the mean time the old gentleman had stood, bareheaded and motionless, in the centre of the room; ‘that I have half a mind to ask you where the other six are—only that would be a joke, and I know I should spoil it. Very near though,’ murmured the Carrier, with a chuckle; ‘very near!’

The Stranger, who had long white hair, good features, singularly bold and well defined for an old man, and dark, bright, penetrating eyes, looked round with a smile, and saluted the Carrier’s wife by gravely inclining his head.

His garb was very quaint and odd—a long, long way behind the time. Its hue was brown, all over. In his hand he held a great brown club or walking–stick; and striking this upon the floor, it fell asunder, and became a chair. On which he sat down, quite composedly.

‘There!’ said the Carrier, turning to his wife. ‘That’s the way I found him, sitting by the roadside! Upright as a milestone. And almost as deaf.’

‘Sitting in the open air, John!’

‘In the open air,’ replied the Carrier, ‘just at dusk. “Carriage Paid,” he said; and gave me eighteenpence. Then he got in. And there he is.’

‘He’s going, John, I think!’

Not at all. He was only going to speak.

‘If you please, I was to be left till called for,’ said the Stranger, mildly. ‘Don’t mind me.’

With that, he took a pair of spectacles from one of his large pockets, and a book from another, and leisurely began to read. Making no more of Boxer than if he had been a house lamb!

The Carrier and his wife exchanged a look of perplexity. The Stranger raised his head; and glancing from the latter to the former, said,

‘Your daughter, my good friend?’

‘Wife,’ returned John.

‘Niece?’ said the Stranger.

‘Wife,’ roared John.

‘Indeed?’ observed the Stranger. ‘Surely? Very young!’

He quietly turned over, and resumed his reading. But, before he could have read two lines, he again interrupted himself to say:

‘Baby, yours?’

John gave him a gigantic nod; equivalent to an answer in the affirmative, delivered through a speaking trumpet.

‘Girl?’

‘Bo–o–oy!’ roared John.

‘Also very young, eh?’

Mrs. Peerybingle instantly struck in. ‘Two months and three da–ays! Vaccinated just six weeks ago–o! Took very fine–ly! Considered, by the doctor, a remarkably beautiful chi–ild! Equal to the general run of children at five months o–old! Takes notice, in a way quite wonderful! May seem impossible to you, but feels his legs al–ready!’

Here the breathless little mother, who had been shrieking these short sentences into the old man’s ear, until her pretty face was crimsoned, held up the Baby before him as a stubborn and triumphant fact; while Tilly Slowboy, with a melodious cry of ‘Ketcher, Ketcher’—which sounded like some unknown words, adapted to a popular Sneeze—performed some cow–like gambols round that all unconscious Innocent.

‘Hark! He’s called for, sure enough,’ said John. ‘There’s somebody at the door. Open it, Tilly.’

Before she could reach it, however, it was opened from without; being a primitive sort of door, with a latch, that any one could lift if he chose—and a good many people did choose, for all kinds of neighbours liked to have a cheerful word or two with the Carrier, though he was no great talker himself. Being opened, it gave admission to a little, meagre, thoughtful, dingy–faced man, who seemed to have made himself a great–coat from the sack–cloth covering of some old box; for, when he turned to shut the door, and keep the weather out, he disclosed upon the back of that garment, the inscription G & T in large black capitals. Also the word glass in bold characters.

‘Good evening, John!’ said the little man. ‘Good evening, Mum. Good evening, Tilly. Good evening, Unbeknown! How’s Baby, Mum? Boxer’s pretty well I hope?’

‘All thriving, Caleb,’ replied Dot. ‘I am sure you need only look at the dear child, for one, to know that.’

‘And I’m sure I need only look at you for another,’ said Caleb.

He didn’t look at her though; he had a wandering and thoughtful eye which seemed to be always projecting itself into some other time and place, no matter what he said; a description which will equally apply to his voice.

‘Or at John for another,’ said Caleb. ‘Or at Tilly, as far as that goes. Or certainly at Boxer.’

‘Busy just now, Caleb?’ asked the Carrier.

‘Why, pretty well, John,’ he returned, with the distraught air of a man who was casting about for the Philosopher’s stone, at least. ‘Pretty much so. There’s rather a run on Noah’s Arks at present. I could have wished to improve upon the Family, but I don’t see how it’s to be done at the price. It would be a satisfaction to one’s mind, to make it clearer which was Shems and Hams, and which was Wives. Flies an’t on that scale neither, as compared with elephants you know! Ah! well! Have you got anything in the parcel line for me, John?’

The Carrier put his hand into a pocket of the coat he had taken off; and brought out, carefully preserved in moss and paper, a tiny flower–pot.

‘There it is!’ he said, adjusting it with great care. ‘Not so much as a leaf damaged. Full of buds!’

Caleb’s dull eye brightened, as he took it, and thanked him.

‘Dear, Caleb,’ said the Carrier. ‘Very dear at this season.’

‘Never mind that. It would be cheap to me, whatever it cost,’ returned the little man. ‘Anything else, John?’

‘A small box,’ replied the Carrier. ‘Here you are!’

‘“For Caleb Plummer,”’ said the little man, spelling out the direction. ‘“With Cash.” With Cash, John? I don’t think it’s for me.’

‘With Care,’ returned the Carrier, looking over his shoulder. ‘Where do you make out cash?’

‘Oh! To be sure!’ said Caleb. ‘It’s all right. With care! Yes, yes; that’s mine. It might have been with cash, indeed, if my dear Boy in the Golden South Americas had lived, John. You loved him like a son; didn’t you? You needn’t say you did. I know, of course. “Caleb Plummer. With care.” Yes, yes, it’s all right. It’s a box of dolls’ eyes for my daughter’s work. I wish it was her own sight in a box, John.’

‘I wish it was, or could be!’ cried the Carrier.

‘Thank’ee,’ said the little man. ‘You speak very hearty. To think that she should never see the Dolls—and them a–staring at her, so bold, all day long! That’s where it cuts. What’s the damage, John?’

‘I’ll damage you,’ said John, ‘if you inquire. Dot! Very near?’

‘Well! it’s like you to say so,’ observed the little man. ‘It’s your kind way. Let me see. I think that’s all.’

‘I think not,’ said the Carrier. ‘Try again.’

‘Something for our Governor, eh?’ said Caleb, after pondering a little while. ‘To be sure. That’s what I came for; but my head’s so running on them Arks and things! He hasn’t been here, has he?’

‘Not he,’ returned the Carrier. ‘He’s too busy, courting.’

‘He’s coming round though,’ said Caleb; ‘for he told me to keep on the near side of the road going home, and it was ten to one he’d take me up. I had better go, by the bye.—You couldn’t have the goodness to let me pinch Boxer’s tail, Mum, for half a moment, could you?’

‘Why, Caleb! what a question!’

‘Oh never mind, Mum,’ said the little man. ‘He mightn’t like it perhaps. There’

s a small order just come in, for barking dogs; and I should wish to go as close to Natur’ as I could, for sixpence. That’s all. Never mind, Mum.’

It happened opportunely, that Boxer, without receiving the proposed stimulus, began to bark with great zeal. But, as this implied the approach of some new visitor, Caleb, postponing his study from the life to a more convenient season, shouldered the round box, and took a hurried leave. He might have spared himself the trouble, for he met the visitor upon the threshold.

‘Oh! You are here, are you? Wait a bit. I’ll take you home. John Peerybingle, my service to you. More of my service to your pretty wife. Handsomer every day! Better too, if possible! And younger,’ mused the speaker, in a low voice; ‘that’s the Devil of it!’

‘I should be astonished at your paying compliments, Mr. Tackleton,’ said Dot, not with the best grace in the world; ‘but for your condition.’

‘You know all about it then?’

‘I have got myself to believe it, somehow,’ said Dot.

‘After a hard struggle, I suppose?’

‘Very.’

Tackleton the Toy–merchant, pretty generally known as Gruff and Tackleton—for that was the firm, though Gruff had been bought out long ago; only leaving his name, and as some said his nature, according to its Dictionary meaning, in the business—Tackleton the Toy–merchant, was a man whose vocation had been quite misunderstood by his Parents and Guardians. If they had made him a Money Lender, or a sharp Attorney, or a Sheriff’s Officer, or a Broker, he might have sown his discontented oats in his youth, and, after having had the full run of himself in ill–natured transactions, might have turned out amiable, at last, for the sake of a little freshness and novelty. But, cramped and chafing in the peaceable pursuit of toy–making, he was a domestic Ogre, who had been living on children all his life, and was their implacable enemy. He despised all toys; wouldn’t have bought one for the world; delighted, in his malice, to insinuate grim expressions into the faces of brown–paper farmers who drove pigs to market, bellmen who advertised lost lawyers’ consciences, movable old ladies who darned stockings or carved pies; and other like samples of his stock in trade. In appalling masks; hideous, hairy, red–eyed Jacks in Boxes; Vampire Kites; demoniacal Tumblers who wouldn’t lie down, and were perpetually flying forward, to stare infants out of countenance; his soul perfectly revelled. They were his only relief, and safety–valve. He was great in such inventions. Anything suggestive of a Pony–nightmare was delicious to him. He had even lost money (and he took to that toy very kindly) by getting up Goblin slides for magic–lanterns, whereon the Powers of Darkness were depicted as a sort of supernatural shell–fish, with human faces. In intensifying the portraiture of Giants, he had sunk quite a little capital; and, though no painter himself, he could indicate, for the instruction of his artists, with a piece of chalk, a certain furtive leer for the countenances of those monsters, which was safe to destroy the peace of mind of any young gentleman between the ages of six and eleven, for the whole Christmas or Midsummer Vacation.

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

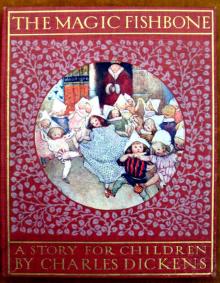

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories