- Home

- Charles Dickens

Speeches: Literary & Social Page 2

Speeches: Literary & Social Read online

Page 2

Gentlemen, talking of my friends in America, brings me back, naturally and of course, to you. Coming back to you, and being thereby reminded of the pleasure we have in store in hearing the gentlemen who sit about me, I arrive by the easiest, though not by the shortest course in the world, at the end of what I have to say. But before I sit down, there is one topic on which I am desirous to lay particular stress. It has, or should have, a strong interest for us all, since to its literature every country must look for one great means of refining and improving its people, and one great source of national pride and honour. You have in America great writers - great writers - who will live in all time, and are as familiar to our lips as household words. Deriving (as they all do in a greater or less degree, in their several walks) their inspiration from the stupendous country that gave them birth, they diffuse a better knowledge of it, and a higher love for it, all over the civilized world. I take leave to say, in the presence of some of those gentleman, that I hope the time is not far distant when they, in America, will receive of right some substantial profit and return in England from their labours; and when we, in England, shall receive some substantial profit and return in America for ours. Pray do not misunderstand me. Securing to myself from day to day the means of an honourable subsistence, I would rather have the affectionate regard of my fellow men, than I would have heaps and mines of gold. But the two things do not seem to me incompatible. They cannot be, for nothing good is incompatible with justice; there must be an international arrangement in this respect: England has done her part, and I am confident that the time is not far distant when America will do hers. It becomes the character of a great country; FIRSTLY, because it is justice; SECONDLY, because without it you never can have, and keep, a literature of your own.

Gentlemen, I thank you with feelings of gratitude, such as are not often awakened, and can never be expressed. As I understand it to be the pleasant custom here to finish with a toast, I would beg to give you: AMERICA AND ENGLAND, and may they never have any division but the Atlantic between them.

SPEECH IV

Speech: February 7, 1842

GENTLEMEN, - To say that I thank you for the earnest manner in which you have drunk the toast just now so eloquently proposed to you - to say that I give you back your kind wishes and good feelings with more than compound interest; and that I feel how dumb and powerless the best acknowledgments would be beside such genial hospitality as yours, is nothing. To say that in this winter season, flowers have sprung up in every footstep's length of the path which has brought me here; that no country ever smiled more pleasantly than yours has smiled on me, and that I have rarely looked upon a brighter summer prospect than that which lies before me now, is nothing.

But it is something to be no stranger in a strange place - to feel, sitting at a board for the first time, the ease and affection of an old guest, and to be at once on such intimate terms with the family as to have a homely, genuine interest in its every member - it is, I say, something to be in this novel and happy frame of mind. And, as it is of your creation, and owes its being to you, I have no reluctance in urging it as a reason why, in addressing you, I should not so much consult the form and fashion of my speech, as I should employ that universal language of the heart, which you, and such as you, best teach, and best can understand. Gentlemen, in that universal language - common to you in America, and to us in England, as that younger mother-tongue, which, by the means of, and through the happy union of our two great countries, shall be spoken ages hence, by land and sea, over the wide surface of the globe - I thank you.

I had occasion to say the other night in Boston, as I have more than once had occasion to remark before, that it is not easy for an author to speak of his own books. If the task be a difficult one at any time, its difficulty, certainly, is not diminished when a frequent recurrence to the same theme has left one nothing new to say. Still, I feel that, in a company like this, and especially after what has been said by the President, that I ought not to pass lightly over those labours of love, which, if they had no other merit, have been the happy means of bringing us together.

It has been often observed, that you cannot judge of an author's personal character from his writings. It may be that you cannot. I think it very likely, for many reasons, that you cannot. But, at least, a reader will rise from the perusal of a book with some defined and tangible idea of the writer's moral creed and broad purposes, if he has any at all; and it is probable enough that he may like to have this idea confirmed from the author's lips, or dissipated by his explanation. Gentlemen, my moral creed - which is a very wide and comprehensive one, and includes all sects and parties - is very easily summed up. I have faith, and I wish to diffuse faith in the existence - yes, of beautiful things, even in those conditions of society, which are so degenerate, degraded, and forlorn, that, at first sight, it would seem as though they could not be described but by a strange and terrible reversal of the words of Scripture, "God said, Let there be light, and there was none." I take it that we are born, and that we hold our sympathies, hopes, and energies, in trust for the many, and not for the few. That we cannot hold in too strong a light of disgust and contempt, before the view of others, all meanness, falsehood, cruelty, and oppression, of every grade and kind. Above all, that nothing is high, because it is in a high place; and that nothing is low, because it is in a low one. This is the lesson taught us in the great book of nature. This is the lesson which may be read, alike in the bright track of the stars, and in the dusty course of the poorest thing that drags its tiny length upon the ground. This is the lesson ever uppermost in the thoughts of that inspired man, who tells us that there are

"Tongues in the trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything."

Gentlemen, keeping these objects steadily before me, I am at no loss to refer your favour and your generous hospitality back to the right source. While I know, on the one hand, that if, instead of being what it is, this were a land of tyranny and wrong, I should care very little for your smiles or frowns, so I am sure upon the other, that if, instead of being what I am, I were the greatest genius that ever trod the earth, and had diverted myself for the oppression and degradation of mankind, you would despise and reject me. I hope you will, whenever, through such means, I give you the opportunity. Trust me, that, whenever you give me the like occasion, I will return the compliment with interest.

Gentlemen, as I have no secrets from you, in the spirit of confidence you have engendered between us, and as I have made a kind of compact with myself that I never will, while I remain in America, omit an opportunity of referring to a topic in which I and all others of my class on both sides of the water are equally interested - equally interested, there is no difference between us, I would beg leave to whisper in your ear two words: INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT. I use them in no sordid sense, believe me, and those who know me best, best know that. For myself, I would rather that my children, coming after me, trudged in the mud, and knew by the general feeling of society that their father was beloved, and had been of some use, than I would have them ride in their carriages, and know by their banker's books that he was rich. But I do not see, I confess, why one should be obliged to make the choice, or why fame, besides playing that delightful REVEIL for which she is so justly celebrated, should not blow out of her trumpet a few notes of a different kind from those with which she has hitherto contented herself.

It was well observed the other night by a beautiful speaker, whose words went to the heart of every man who heard him, that, if there had existed any law in this respect, Scott might not have sunk beneath the mighty pressure on his brain, but might have lived to add new creatures of his fancy to the crowd which swarm about you in your summer walks, and gather round your winter evening hearths.

As I listened to his words, there came back, fresh upon me, that touching scene in the great man's life, when he lay upon his couch, surrounded by his family, and listened, for the last time, to the rippling

of the river he had so well loved, over its stony bed. I pictured him to myself, faint, wan, dying, crushed both in mind and body by his honourable struggle, and hovering round him the phantoms of his own imagination - Waverley, Ravenswood, Jeanie Deans, Rob Roy, Caleb Balderstone, Dominie Sampson - all the familiar throng - with cavaliers, and Puritans, and Highland chiefs innumerable overflowing the chamber, and fading away in the dim distance beyond. I pictured them, fresh from traversing the world, and hanging down their heads in shame and sorrow, that, from all those lands into which they had carried gladness, instruction, and delight for millions, they brought him not one friendly hand to help to raise him from that sad, sad bed. No, nor brought him from that land in which his own language was spoken, and in every house and hut of which his own books were read in his own tongue, one grateful dollar-piece to buy a garland for his grave. Oh! if every man who goes from here, as many do, to look upon that tomb in Dryburgh Abbey, would but remember this, and bring the recollection home!

Gentlemen, I thank you again, and once again, and many times to that. You have given me a new reason for remembering this day, which is already one of mark in my calendar, it being my birthday; and you have given those who are nearest and dearest to me a new reason for recollecting it with pride and interest. Heaven knows that, although I should grow ever so gray, I shall need nothing to remind me of this epoch in my life. But I am glad to think that from this time you are inseparably connected with every recurrence of this day; and, that on its periodical return, I shall always, in imagination, have the unfading pleasure of entertaining you as my guests, in return for the gratification you have afforded me to- night.

SPEECH V

Speech: New York, February 18, 1842

At a dinner presided over by Washington Irving, when nearly eight hundred of the most distinguished citizens of New York were present, "Charles Dickens, the Literary Guest of the Nation," having been "proferred as a sentiment" by the Chairman, Mr. Dickens rose, and spoke as follows:

GENTLEMEN, - I don't know how to thank you - I really don't know how. You would naturally suppose that my former experience would have given me this power, and that the difficulties in my way would have been diminished; but I assure you the fact is exactly the reverse, and I have completely baulked the ancient proverb that "a rolling stone gathers no moss;" and in my progress to this city I have collected such a weight of obligations and acknowledgment - I have picked up such an enormous mass of fresh moss at every point, and was so struck by the brilliant scenes of Monday night, that I thought I could never by any possibility grow any bigger. I have made, continually, new accumulations to such an extent that I am compelled to stand still, and can roll no more!

Gentlemen, we learn from the authorities, that, when fairy stories, or balls, or rolls of thread, stopped of their own accord - as I do not - it presaged some great catastrophe near at hand. The precedent holds good in this case. When I have remembered the short time I have before me to spend in this land of mighty interests, and the poor opportunity I can at best have of acquiring a knowledge of, and forming an acquaintance with it, I have felt it almost a duty to decline the honours you so generously heap upon me, and pass more quietly among you. For Argus himself, though he had but one mouth for his hundred eyes, would have found the reception of a public entertainment once a-week too much for his greatest activity; and, as I would lose no scrap of the rich instruction and the delightful knowledge which meet me on every hand, (and already I have gleaned a great deal from your hospitals and common jails), - I have resolved to take up my staff, and go my way rejoicing, and for the future to shake hands with America, not at parties but at home; and, therefore, gentlemen, I say to-night, with a full heart, and an honest purpose, and grateful feelings, that I bear, and shall ever bear, a deep sense of your kind, your affectionate and your noble greeting, which it is utterly impossible to convey in words. No European sky without, and no cheerful home or well-warmed room within shall ever shut out this land from my vision. I shall often hear your words of welcome in my quiet room, and oftenest when most quiet; and shall see your faces in the blazing fire. If I should live to grow old, the scenes of this and other evenings will shine as brightly to my dull eyes fifty years hence as now; and the honours you bestow upon me shall be well remembered and paid back in my undying love, and honest endeavours for the good of my race.

Gentlemen, one other word with reference to this first person singular, and then I shall close. I came here in an open, honest, and confiding spirit, if ever man did, and because I felt a deep sympathy in your land; had I felt otherwise, I should have kept away. As I came here, and am here, without the least admixture of one-hundredth part of one grain of base alloy, without one feeling of unworthy reference to self in any respect, I claim, in regard to the past, for the last time, my right in reason, in truth, and in justice, to approach, as I have done on two former occasions, a question of literary interest. I claim that justice be done; and I prefer this claim as one who has a right to speak and be heard. I have only to add that I shall be as true to you as you have been to me. I recognize in your enthusiastic approval of the creatures of my fancy, your enlightened care for the happiness of the many, your tender regard for the afflicted, your sympathy for the downcast, your plans for correcting and improving the bad, and for encouraging the good; and to advance these great objects shall be, to the end of my life, my earnest endeavour, to the extent of my humble ability. Having said thus much with reference to myself, I shall have the pleasure of saying a few words with reference to somebody else.

There is in this city a gentleman who, at the reception of one of my books - I well remember it was the Old Curiosity Shop - wrote to me in England a letter so generous, so affectionate, and so manly, that if I had written the book under every circumstance of disappointment, of discouragement, and difficulty, instead of the reverse, I should have found in the receipt of that letter my best and most happy reward. I answered him, and he answered me, and so we kept shaking hands autographically, as if no ocean rolled between us. I came here to this city eager to see him, and LAYING HIS HAND IT UPON IRVING'S SHOULDER here he sits! I need not tell you how happy and delighted I am to see him here to-night in this capacity.

Washington Irving! Why, gentlemen, I don't go upstairs to bed two nights out of the seven - as a very creditable witness near at hand can testify - I say I do not go to bed two nights out of the seven without taking Washington Irving under my arm; and, when I don't take him, I take his own brother, Oliver Goldsmith. Washington Irving! Why, of whom but him was I thinking the other day when I came up by the Hog's Back, the Frying Pan, Hell Gate, and all these places? Why, when, not long ago, I visited Shakespeare's birthplace, and went beneath the roof where he first saw light, whose name but HIS was pointed out to me upon the wall? Washington Irving - Diedrich Knickerbocker - Geoffrey Crayon - why, where can you go that they have not been there before? Is there an English farm - is there an English stream, an English city, or an English country-seat, where they have not been? Is there no Bracebridge Hall in existence? Has it no ancient shades or quiet streets?

In bygone times, when Irving left that Hall, he left sitting in an old oak chair, in a small parlour of the Boar's Head, a little man with a red nose, and an oilskin hat. When I came away he was sitting there still! - not a man LIKE him, but the same man - with the nose of immortal redness and the hat of an undying glaze! Crayon, while there, was on terms of intimacy with a certain radical fellow, who used to go about, with a hatful of newspapers, wofully out at elbows, and with a coat of great antiquity. Why, gentlemen, I know that man - Tibbles the elder, and he has not changed a hair; and, when I came away, he charged me to give his best respects to Washington Irving!

Leaving the town and the rustic life of England - forgetting this man, if we can - putting out of mind the country church-yard and the broken heart - let us cross the water again, and ask who has associated himself most closely with the Italian peasantry and the bandits of the Pyrenees? When the trave

ller enters his little chamber beyond the Alps - listening to the dim echoes of the long passages and spacious corridors - damp, and gloomy, and cold - as he hears the tempest beating with fury against his window, and gazes at the curtains, dark, and heavy, and covered with mould - and when all the ghost-stories that ever were told come up before him - amid all his thick-coming fancies, whom does he think of? Washington Irving.

Go farther still: go to the Moorish Mountains, sparkling full in the moonlight - go among the water-carriers and the village gossips, living still as in days of old - and who has travelled among them before you, and peopled the Alhambra and made eloquent its shadows? Who awakes there a voice from every hill and in every cavern, and bids legends, which for centuries have slept a dreamless sleep, or watched unwinkingly, start up and pass before you in all their life and glory?

But leaving this again, who embarked with Columbus upon his gallant ship, traversed with him the dark and mighty ocean, leaped upon the land and planted there the flag of Spain, but this same man, now sitting by my side? And being here at home again, who is a more fit companion for money-diggers? and what pen but his has made Rip Van Winkle, playing at nine-pins on that thundering afternoon, as much part and parcel of the Catskill Mountains as any tree or crag that they can boast?

But these are topics familiar from my boyhood, and which I am apt to pursue; and lest I should be tempted now to talk too long about them, I will, in conclusion, give you a sentiment, most appropriate, I am sure, in the presence of such writers as Bryant, Halleck, and - but I suppose I must not mention the ladies here -

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

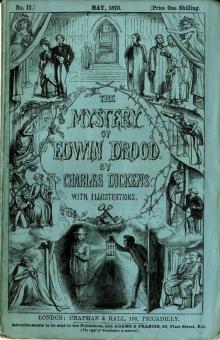

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

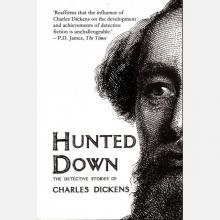

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

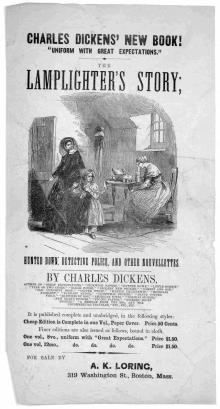

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

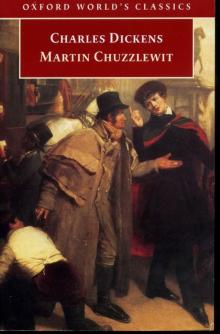

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

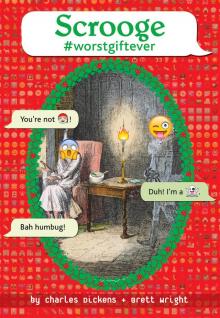

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories