- Home

- Charles Dickens

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Page 3

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Read online

Page 3

Chapter 2

'A strange story!' said the man who had been the cause of thenarration.--'Stranger still if it comes about as you predict. Is thatall?'

A question so unexpected, nettled Solomon Daisy not a little. By dint ofrelating the story very often, and ornamenting it (according to villagereport) with a few flourishes suggested by the various hearers from timeto time, he had come by degrees to tell it with great effect; and 'Isthat all?' after the climax, was not what he was accustomed to.

'Is that all?' he repeated, 'yes, that's all, sir. And enough too, Ithink.'

'I think so too. My horse, young man! He is but a hack hired from aroadside posting house, but he must carry me to London to-night.'

'To-night!' said Joe.

'To-night,' returned the other. 'What do you stare at? This tavernwould seem to be a house of call for all the gaping idlers of theneighbourhood!'

At this remark, which evidently had reference to the scrutiny he hadundergone, as mentioned in the foregoing chapter, the eyes of JohnWillet and his friends were diverted with marvellous rapidity to thecopper boiler again. Not so with Joe, who, being a mettlesome fellow,returned the stranger's angry glance with a steady look, and rejoined:

'It is not a very bold thing to wonder at your going on to-night. Surelyyou have been asked such a harmless question in an inn before, and inbetter weather than this. I thought you mightn't know the way, as youseem strange to this part.'

'The way--' repeated the other, irritably.

'Yes. DO you know it?'

'I'll--humph!--I'll find it,' replied the man, waving his hand andturning on his heel. 'Landlord, take the reckoning here.'

John Willet did as he was desired; for on that point he was seldom slow,except in the particulars of giving change, and testing the goodness ofany piece of coin that was proffered to him, by the application of histeeth or his tongue, or some other test, or in doubtful cases, by a longseries of tests terminating in its rejection. The guest then wrapped hisgarments about him so as to shelter himself as effectually as he couldfrom the rough weather, and without any word or sign of farewell betookhimself to the stableyard. Here Joe (who had left the room on theconclusion of their short dialogue) was protecting himself and the horsefrom the rain under the shelter of an old penthouse roof.

'He's pretty much of my opinion,' said Joe, patting the horse upon theneck. 'I'll wager that your stopping here to-night would please himbetter than it would please me.'

'He and I are of different opinions, as we have been more than once onour way here,' was the short reply.

'So I was thinking before you came out, for he has felt your spurs, poorbeast.'

The stranger adjusted his coat-collar about his face, and made noanswer.

'You'll know me again, I see,' he said, marking the young fellow'searnest gaze, when he had sprung into the saddle.

'The man's worth knowing, master, who travels a road he don't know,mounted on a jaded horse, and leaves good quarters to do it on such anight as this.'

'You have sharp eyes and a sharp tongue, I find.'

'Both I hope by nature, but the last grows rusty sometimes for want ofusing.'

'Use the first less too, and keep their sharpness for your sweethearts,boy,' said the man.

So saying he shook his hand from the bridle, struck him roughly on thehead with the butt end of his whip, and galloped away; dashing throughthe mud and darkness with a headlong speed, which few badly mountedhorsemen would have cared to venture, even had they been thoroughlyacquainted with the country; and which, to one who knew nothing of theway he rode, was attended at every step with great hazard and danger.

The roads, even within twelve miles of London, were at that timeill paved, seldom repaired, and very badly made. The way this ridertraversed had been ploughed up by the wheels of heavy waggons, andrendered rotten by the frosts and thaws of the preceding winter, orpossibly of many winters. Great holes and gaps had been worn into thesoil, which, being now filled with water from the late rains, were noteasily distinguishable even by day; and a plunge into any one of themmight have brought down a surer-footed horse than the poor beast nowurged forward to the utmost extent of his powers. Sharp flints andstones rolled from under his hoofs continually; the rider could scarcelysee beyond the animal's head, or farther on either side than his ownarm would have extended. At that time, too, all the roads in theneighbourhood of the metropolis were infested by footpads or highwaymen,and it was a night, of all others, in which any evil-disposed person ofthis class might have pursued his unlawful calling with little fear ofdetection.

Still, the traveller dashed forward at the same reckless pace,regardless alike of the dirt and wet which flew about his head, theprofound darkness of the night, and the probability of encounteringsome desperate characters abroad. At every turn and angle, even wherea deviation from the direct course might have been least expected, andcould not possibly be seen until he was close upon it, he guided thebridle with an unerring hand, and kept the middle of the road. Thus hesped onward, raising himself in the stirrups, leaning his body forwarduntil it almost touched the horse's neck, and flourishing his heavy whipabove his head with the fervour of a madman.

There are times when, the elements being in unusual commotion, those whoare bent on daring enterprises, or agitated by great thoughts, whetherof good or evil, feel a mysterious sympathy with the tumult of nature,and are roused into corresponding violence. In the midst of thunder,lightning, and storm, many tremendous deeds have been committed; men,self-possessed before, have given a sudden loose to passions they couldno longer control. The demons of wrath and despair have striven toemulate those who ride the whirlwind and direct the storm; and man,lashed into madness with the roaring winds and boiling waters, hasbecome for the time as wild and merciless as the elements themselves.

Whether the traveller was possessed by thoughts which the fury of thenight had heated and stimulated into a quicker current, or was merelyimpelled by some strong motive to reach his journey's end, on he sweptmore like a hunted phantom than a man, nor checked his pace until,arriving at some cross roads, one of which led by a longer route tothe place whence he had lately started, he bore down so suddenly upon avehicle which was coming towards him, that in the effort to avoid it hewell-nigh pulled his horse upon his haunches, and narrowly escaped beingthrown.

'Yoho!' cried the voice of a man. 'What's that? Who goes there?'

'A friend!' replied the traveller.

'A friend!' repeated the voice. 'Who calls himself a friend and rideslike that, abusing Heaven's gifts in the shape of horseflesh, andendangering, not only his own neck (which might be no great matter) butthe necks of other people?'

'You have a lantern there, I see,' said the traveller dismounting, 'lendit me for a moment. You have wounded my horse, I think, with your shaftor wheel.'

'Wounded him!' cried the other, 'if I haven't killed him, it's no faultof yours. What do you mean by galloping along the king's highway likethat, eh?'

'Give me the light,' returned the traveller, snatching it from his hand,'and don't ask idle questions of a man who is in no mood for talking.'

'If you had said you were in no mood for talking before, I shouldperhaps have been in no mood for lighting,' said the voice. 'Hows'everas it's the poor horse that's damaged and not you, one of you is welcometo the light at all events--but it's not the crusty one.'

The traveller returned no answer to this speech, but holding the lightnear to his panting and reeking beast, examined him in limb and carcass.Meanwhile, the other man sat very composedly in his vehicle, which wasa kind of chaise with a depository for a large bag of tools, and watchedhis proceedings with a careful eye.

The looker-on was a round, red-faced, sturdy yeoman, with a double chin,and a voice husky with good living, good sleeping, good humour, and goodhealth. He was past the prime of life, but Father Time is not always ahard parent, and, though he tarries for none of his children, often layshis hand lightly upon those who have used him well;

making them old menand women inexorably enough, but leaving their hearts and spirits youngand in full vigour. With such people the grey head is but the impressionof the old fellow's hand in giving them his blessing, and every wrinklebut a notch in the quiet calendar of a well-spent life.

The person whom the traveller had so abruptly encountered was ofthis kind: bluff, hale, hearty, and in a green old age: at peace withhimself, and evidently disposed to be so with all the world. Althoughmuffled up in divers coats and handkerchiefs--one of which, passed overhis crown, and tied in a convenient crease of his double chin, securedhis three-cornered hat and bob-wig from blowing off his head--therewas no disguising his plump and comfortable figure; neither did certaindirty finger-marks upon his face give it any other than an odd andcomical expression, through which its natural good humour shone withundiminished lustre.

'He is not hurt,' said the traveller at length, raising his head and thelantern together.

'You have found that out at last, have you?' rejoined the old man. 'Myeyes have seen more light than yours, but I wouldn't change with you.'

'What do you mean?'

'Mean! I could have told you he wasn't hurt, five minutes ago. Give methe light, friend; ride forward at a gentler pace; and good night.'

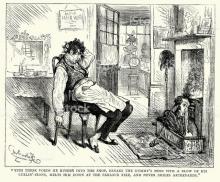

In handing up the lantern, the man necessarily cast its rays full on thespeaker's face. Their eyes met at the instant. He suddenly dropped itand crushed it with his foot.

'Did you never see a locksmith before, that you start as if you had comeupon a ghost?' cried the old man in the chaise, 'or is this,' he addedhastily, thrusting his hand into the tool basket and drawing out ahammer, 'a scheme for robbing me? I know these roads, friend. When Itravel them, I carry nothing but a few shillings, and not a crown'sworth of them. I tell you plainly, to save us both trouble, that there'snothing to be got from me but a pretty stout arm considering my years,and this tool, which, mayhap from long acquaintance with, I can usepretty briskly. You shall not have it all your own way, I promise you,if you play at that game. With these words he stood upon the defensive.

'I am not what you take me for, Gabriel Varden,' replied the other.

'Then what and who are you?' returned the locksmith. 'You know my name,it seems. Let me know yours.'

'I have not gained the information from any confidence of yours, butfrom the inscription on your cart which tells it to all the town,'replied the traveller.

'You have better eyes for that than you had for your horse, then,' saidVarden, descending nimbly from his chaise; 'who are you? Let me see yourface.'

While the locksmith alighted, the traveller had regained his saddle,from which he now confronted the old man, who, moving as the horse movedin chafing under the tightened rein, kept close beside him.

'Let me see your face, I say.'

'Stand off!'

'No masquerading tricks,' said the locksmith, 'and tales at the clubto-morrow, how Gabriel Varden was frightened by a surly voice and a darknight. Stand--let me see your face.'

Finding that further resistance would only involve him in a personalstruggle with an antagonist by no means to be despised, the travellerthrew back his coat, and stooping down looked steadily at the locksmith.

Perhaps two men more powerfully contrasted, never opposed each otherface to face. The ruddy features of the locksmith so set off andheightened the excessive paleness of the man on horseback, that helooked like a bloodless ghost, while the moisture, which hard riding hadbrought out upon his skin, hung there in dark and heavy drops, like dewsof agony and death. The countenance of the old locksmith lighted up withthe smile of one expecting to detect in this unpromising stranger somelatent roguery of eye or lip, which should reveal a familiar person inthat arch disguise, and spoil his jest. The face of the other, sullenand fierce, but shrinking too, was that of a man who stood at bay; whilehis firmly closed jaws, his puckered mouth, and more than all a certainstealthy motion of the hand within his breast, seemed to announce adesperate purpose very foreign to acting, or child's play.

Thus they regarded each other for some time, in silence.

'Humph!' he said when he had scanned his features; 'I don't know you.'

'Don't desire to?'--returned the other, muffling himself as before.

'I don't,' said Gabriel; 'to be plain with you, friend, you don't carryin your countenance a letter of recommendation.'

'It's not my wish,' said the traveller. 'My humour is to be avoided.'

'Well,' said the locksmith bluntly, 'I think you'll have your humour.'

'I will, at any cost,' rejoined the traveller. 'In proof of it, lay thisto heart--that you were never in such peril of your life as you havebeen within these few moments; when you are within five minutes ofbreathing your last, you will not be nearer death than you have beento-night!'

'Aye!' said the sturdy locksmith.

'Aye! and a violent death.'

'From whose hand?'

'From mine,' replied the traveller.

With that he put spurs to his horse, and rode away; at first plashingheavily through the mire at a smart trot, but gradually increasing inspeed until the last sound of his horse's hoofs died away upon the wind;when he was again hurrying on at the same furious gallop, which had beenhis pace when the locksmith first encountered him.

Gabriel Varden remained standing in the road with the broken lantern inhis hand, listening in stupefied silence until no sound reached his earbut the moaning of the wind, and the fast-falling rain; when he struckhimself one or two smart blows in the breast by way of rousing himself,and broke into an exclamation of surprise.

'What in the name of wonder can this fellow be! a madman? a highwayman?a cut-throat? If he had not scoured off so fast, we'd have seen who wasin most danger, he or I. I never nearer death than I have been to-night!I hope I may be no nearer to it for a score of years to come--if so,I'll be content to be no farther from it. My stars!--a pretty brag thisto a stout man--pooh, pooh!'

Gabriel resumed his seat, and looked wistfully up the road by which thetraveller had come; murmuring in a half whisper:

'The Maypole--two miles to the Maypole. I came the other road from theWarren after a long day's work at locks and bells, on purpose that Ishould not come by the Maypole and break my promise to Martha by lookingin--there's resolution! It would be dangerous to go on to London withouta light; and it's four miles, and a good half mile besides, to theHalfway-House; and between this and that is the very place where oneneeds a light most. Two miles to the Maypole! I told Martha I wouldn't;I said I wouldn't, and I didn't--there's resolution!'

Repeating these two last words very often, as if to compensate for thelittle resolution he was going to show by piquing himself on the greatresolution he had shown, Gabriel Varden quietly turned back, determiningto get a light at the Maypole, and to take nothing but a light.

When he got to the Maypole, however, and Joe, responding to hiswell-known hail, came running out to the horse's head, leaving the dooropen behind him, and disclosing a delicious perspective of warmth andbrightness--when the ruddy gleam of the fire, streaming through the oldred curtains of the common room, seemed to bring with it, as part ofitself, a pleasant hum of voices, and a fragrant odour of steaming grogand rare tobacco, all steeped as it were in the cheerful glow--when theshadows, flitting across the curtain, showed that those inside had risenfrom their snug seats, and were making room in the snuggest corner (howwell he knew that corner!) for the honest locksmith, and a broad glare,suddenly streaming up, bespoke the goodness of the crackling log fromwhich a brilliant train of sparks was doubtless at that moment whirlingup the chimney in honour of his coming--when, superadded to theseenticements, there stole upon him from the distant kitchen a gentlesound of frying, with a musical clatter of plates and dishes, and asavoury smell that made even the boisterous wind a perfume--Gabrielfelt his firmness oozing rapidly away. He tried to look stoically at thetavern, but his features would relax into a look of fondness. He turnedhis head the other way, and the cold black country seemed to frown himoff

, and drive him for a refuge into its hospitable arms.

'The merciful man, Joe,' said the locksmith, 'is merciful to his beast.I'll get out for a little while.'

And how natural it was to get out! And how unnatural it seemed for asober man to be plodding wearily along through miry roads, encounteringthe rude buffets of the wind and pelting of the rain, when there wasa clean floor covered with crisp white sand, a well swept hearth, ablazing fire, a table decorated with white cloth, bright pewter flagons,and other tempting preparations for a well-cooked meal--when there werethese things, and company disposed to make the most of them, all readyto his hand, and entreating him to enjoyment!

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories