- Home

- Charles Dickens

Sketches by Boz Page 31

Sketches by Boz Read online

Page 31

The quarter-day arrived at last—we say at last, because quarterdays are as eccentric as comets: moving wonderfully quick when you have a good deal to pay, and marvellously slow when you have a little to receive. Mr. Thomas Potter and Mr. Robert Smithers met by appointment to begin the evening with a dinner; and a nice, snug, comfortable dinner they had, consisting of a little procession of four chops and four kidneys, following each other, supported on either side by a pot of the real draught stout, and attended by divers cushions of bread, and wedges of cheese.

When the cloth was removed, Mr. Thomas Potter ordered the waiter to bring in, two goes of his best Scotch whiskey, with warm water and sugar, and a couple of his “very mildest” Havannahs, which the waiter did. Mr. Thomas Potter mixed his grog, and lighted his cigar; Mr. Robert Smithers did the same; and then, Mr. Thomas Potter jocularly proposed as the first toast, “the abolition of all offices whatever” (not sinecures, but counting-houses), which was immediately drunk by Mr. Robert Smithers, with enthusiastic applause. So they went on, talking politics, puffing cigars, and sipping whiskey-and-water, until the “goes”—most appropriately so called—were both gone, which Mr. Robert Smithers perceiving, immediately ordered in two more goes of the best Scotch whiskey, and two more of the very mildest Havannahs; and the goes kept coming in, and the mild Havannahs kept going out, until, what with the drinking, and lighting, and puffing, and the stale ashes on the table, and the tallow-grease on the cigars, Mr. Robert Smithers began to doubt the mildness of the Havannahs, and to feel very much as if he had been sitting in a hackney-coach with his back to the horses.

As to Mr. Thomas Potter, he WOULD keep laughing out loud, and volunteering inarticulate declarations that he was “all right;” in proof of which, he feebly bespoke the evening paper after the next gentleman, but finding it a matter of some difficulty to discover any news in its columns, or to ascertain distinctly whether it had any columns at all, walked slowly out to look for the moon, and, after coming back quite pale with looking up at the sky so long, and attempting to express mirth at Mr. Robert Smithers having fallen asleep, by various galvanic chuckles, laid his head on his arm, and went to sleep also. When he awoke again, Mr. Robert Smithers awoke too, and they both very gravely agreed that it was extremely unwise to eat so many pickled walnuts with the chops, as it was a notorious fact that they always made people queer and sleepy; indeed, if it had not been for the whiskey and cigars, there was no knowing what harm they mightn't have done “em. So they took some coffee, and after paying the bill,—twelve and twopence the dinner, and the odd tenpence for the waiter—thirteen shillings in all—started out on their expedition to manufacture a night.

It was just half-past eight, so they thought they couldn't do better than go at half-price to the slips at the City Theatre, which they did accordingly. Mr. Robert Smithers, who had become extremely poetical after the settlement of the bill, enlivening the walk by informing Mr. Thomas Potter in confidence that he felt an inward presentiment of approaching dissolution, and subsequently embellishing the theatre, by falling asleep with his head and both arms gracefully drooping over the front of the boxes.

Such was the quiet demeanour of the unassuming Smithers, and such were the happy effects of Scotch whiskey and Havannahs on that interesting person! But Mr. Thomas Potter, whose great aim it was to be considered as a “knowing card,” a “fast-goer,” and so forth, conducted himself in a very different manner, and commenced going very fast indeed—rather too fast at last, for the patience of the audience to keep pace with him. On his first entry, he contented himself by earnestly calling upon the gentlemen in the gallery to “flare up,” accompanying the demand with another request, expressive of his wish that they would instantaneously “form a union,” both which requisitions were responded to, in the manner most in vogue on such occasions.

“Give that dog a bone!” cried one gentleman in his shirt-sleeves.

“Where have you been a having half a pint of intermediate beer?” cried a second. “Tailor!” screamed a third. “Barber's clerk!” shouted a fourth. “Throw him O-VER!” roared a fifth; while numerous voices concurred in desiring Mr. Thomas Potter to “go home to his mother!” All these taunts Mr. Thomas Potter received with supreme contempt, cocking the low-crowned hat a little more on one side, whenever any reference was made to his personal appearance, and, standing up with his arms a-kimbo, expressing defiance melodramatically.

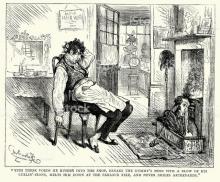

The overture—to which these various sounds had been an AD LIBITUM accompaniment—concluded, the second piece began, and Mr. Thomas Potter, emboldened by impunity, proceeded to behave in a most unprecedented and outrageous manner. First of all, he imitated the shake of the principal female singer; then, groaned at the blue fire; then, affected to be frightened into convulsions of terror at the appearance of the ghost; and, lastly, not only made a running commentary, in an audible voice, upon the dialogue on the stage, but actually awoke Mr. Robert Smithers, who, hearing his companion making a noise, and having a very indistinct notion where he was, or what was required of him, immediately, by way of imitating a good example, set up the most unearthly, unremitting, and appalling howling that ever audience heard. It was too much. “Turn them out!” was the general cry. A noise, as of shuffling of feet, and men being knocked up with violence against wainscoting, was heard: a hurried dialogue of “Come out?”—“I won't!”—“You shall!”—“I shan't!”—“Give me your card, Sir?”—“You're a scoundrel, Sir!” and so forth, succeeded. A round of applause betokened the approbation of the audience, and Mr. Robert Smithers and Mr. Thomas Potter found themselves shot with astonishing swiftness into the road, without having had the trouble of once putting foot to ground during the whole progress of their rapid descent.

Mr. Robert Smithers, being constitutionally one of the slow-goers, and having had quite enough of fast-going, in the course of his recent expulsion, to last until the quarter-day then next ensuing at the very least, had no sooner emerged with his companion from the precincts of Milton-street, than he proceeded to indulge in circuitous references to the beauties of sleep, mingled with distant allusions to the propriety of returning to Islington, and testing the influence of their patent Bramahs over the street-door locks to which they respectively belonged. Mr. Thomas Potter, however, was valorous and peremptory. They had come out to make a night of it: and a night must be made. So Mr. Robert Smithers, who was three parts dull, and the other dismal, despairingly assented; and they went into a wine-vaults, to get materials for assisting them in making a night; where they found a good many young ladies, and various old gentlemen, and a plentiful sprinkling of hackney-coachmen and cab-drivers, all drinking and talking together; and Mr. Thomas Potter and Mr. Robert Smithers drank small glasses of brandy, and large glasses of soda, until they began to have a very confused idea, either of things in general, or of anything in particular; and, when they had done treating themselves they began to treat everybody else; and the rest of the entertainment was a confused mixture of heads and heels, black eyes and blue uniforms, mud and gas-lights, thick doors, and stone paving.

Then, as standard novelists expressively inform us—“all was a blank!” and in the morning the blank was filled up with the words “STATION-HOUSE,” and the station-house was filled up with Mr. Thomas Potter, Mr. Robert Smithers, and the major part of their wine-vault companions of the preceding night, with a comparatively small portion of clothing of any kind. And it was disclosed at the Police-office, to the indignation of the Bench, and the astonishment of the spectators, how one Robert Smithers, aided and abetted by one Thomas Potter, had knocked down and beaten, in divers streets, at different times, five men, four boys, and three women; how the said Thomas Potter had feloniously obtained possession of five door-knockers, two bell-handles, and a bonnet; how Robert Smithers, his friend, had sworn, at least forty pounds” worth of oaths, at the rate of five shillings apiece; terrified whole streets full of Her Majesty's subjects with awful shrieks and alarms of fire; destroyed the uniforms of five police

men; and committed various other atrocities, too numerous to recapitulate. And the magistrate, after an appropriate reprimand, fined Mr. Thomas Potter and Mr. Thomas Smithers five shillings each, for being, what the law vulgarly terms, drunk; and thirty-four pounds for seventeen assaults at forty shillings a-head, with liberty to speak to the prosecutors.

The prosecutors WERE spoken to, and Messrs. Potter and Smithers lived on credit, for a quarter, as best they might; and, although the prosecutors expressed their readiness to be assaulted twice a week, on the same terms, they have never since been detected in “making a night of it.”

CHAPTER XII

THE PRISONERS' VAN

We were passing the corner of Bow-street, on our return from a lounging excursion the other afternoon, when a crowd, assembled round the door of the Police-office, attracted our attention. We turned up the street accordingly. There were thirty or forty people, standing on the pavement and half across the road; and a few stragglers were patiently stationed on the opposite side of the way—all evidently waiting in expectation of some arrival. We waited too, a few minutes, but nothing occurred; so, we turned round to an unshorn, sallow-looking cobbler, who was standing next us with his hands under the bib of his apron, and put the usual question of “What's the matter?” The cobbler eyed us from head to foot, with superlative contempt, and laconically replied “Nuffin.”

Now, we were perfectly aware that if two men stop in the street to look at any given object, or even to gaze in the air, two hundred men will be assembled in no time; but, as we knew very well that no crowd of people could by possibility remain in a street for five minutes without getting up a little amusement among themselves, unless they had some absorbing object in view, the natural inquiry next in order was, “What are all these people waiting here for?”—“Her Majesty's carriage,” replied the cobbler. This was still more extraordinary. We could not imagine what earthly business Her Majesty's carriage could have at the Public Office, Bow-street. We were beginning to ruminate on the possible causes of such an uncommon appearance, when a general exclamation from all the boys in the crowd of “Here's the wan!” caused us to raise our heads, and look up the street.

The covered vehicle, in which prisoners are conveyed from the police-offices to the different prisons, was coming along at full speed. It then occurred to us, for the first time, that Her Majesty's carriage was merely another name for the prisoners” van, conferred upon it, not only by reason of the superior gentility of the term, but because the aforesaid van is maintained at Her Majesty's expense: having been originally started for the exclusive accommodation of ladies and gentlemen under the necessity of visiting the various houses of call known by the general denomination of “Her Majesty's Gaols.”

The van drew up at the office-door, and the people thronged round the steps, just leaving a little alley for the prisoners to pass through. Our friend the cobbler, and the other stragglers, crossed over, and we followed their example. The driver, and another man who had been seated by his side in front of the vehicle, dismounted, and were admitted into the office. The office-door was closed after them, and the crowd were on the tiptoe of expectation.

After a few minutes” delay, the door again opened, and the two first prisoners appeared. They were a couple of girls, of whom the elder—could not be more than sixteen, and the younger of whom had certainly not attained her fourteenth year. That they were sisters, was evident, from the resemblance which still subsisted between them, though two additional years of depravity had fixed their brand upon the elder girl's features, as legibly as if a redhot iron had seared them. They were both gaudily dressed, the younger one especially; and, although there was a strong similarity between them in both respects, which was rendered the more obvious by their being handcuffed together, it is impossible to conceive a greater contrast than the demeanour of the two presented. The younger girl was weeping bitterly—not for display, or in the hope of producing effect, but for very shame: her face was buried in her handkerchief: and her whole manner was but too expressive of bitter and unavailing sorrow.

“How long are you for, Emily?” screamed a red-faced woman in the crowd. “Six weeks and labour,” replied the elder girl with a flaunting laugh; “and that's better than the stone jug anyhow; the mill's a deal better than the Sessions, and here's Bella a-going too for the first time. Hold up your head, you chicken,” she continued, boisterously tearing the other girl's handkerchief away; “Hold up your head, and show “em your face. I an't jealous, but I'm blessed if I an't game!”—“That's right, old gal,” exclaimed a man in a paper cap, who, in common with the greater part of the crowd, had been inexpressibly delighted with this little incident.—“Right!” replied the girl; “ah, to be sure; what's the odds, eh?”—“Come! In with you,” interrupted the driver. “Don't you be in a hurry, coachman,” replied the girl, “and recollect I want to be set down in Cold Bath Fields—large house with a high garden-wall in front; you can't mistake it. Hallo. Bella, where are you going to—you'll pull my precious arm off?” This was addressed to the younger girl, who, in her anxiety to hide herself in the caravan, had ascended the steps first, and forgotten the strain upon the handcuff. “Come down, and let's show you the way.” And after jerking the miserable girl down with a force which made her stagger on the pavement, she got into the vehicle, and was followed by her wretched companion.

These two girls had been thrown upon London streets, their vices and debauchery, by a sordid and rapacious mother. What the younger girl was then, the elder had been once; and what the elder then was, the younger must soon become. A melancholy prospect, but how surely to be realised; a tragic drama, but how often acted! Turn to the prisons and police offices of London —nay, look into the very streets themselves. These things pass before our eyes, day after day, and hour after hour—they have become such matters of course, that they are utterly disregarded. The progress of these girls in crime will be as rapid as the flight of a pestilence, resembling it too in its baneful influence and wide-spreading infection. Step by step, how many wretched females, within the sphere of every man's observation, have become involved in a career of vice, frightful to contemplate; hopeless at its commencement, loathsome and repulsive in its course; friendless, forlorn, and unpitied, at its miserable conclusion!

There were other prisoners—boys of ten, as hardened in vice as men of fifty—a houseless vagrant, going joyfully to prison as a place of food and shelter, handcuffed to a man whose prospects were ruined, character lost, and family rendered destitute, by his first offence. Our curiosity, however, was satisfied. The first group had left an impression on our mind we would gladly have avoided, and would willingly have effaced.

The crowd dispersed; the vehicle rolled away with its load of guilt and misfortune; and we saw no more of the Prisoners” Van.

TALES

CHAPTER I

THE BOARDING-HOUSE.

CHAPTER I.

Mrs. Tibbs was, beyond all dispute, the most tidy, fidgety, thrifty little personage that ever inhaled the smoke of London ; and the house of Mrs. Tibbs was, decidedly, the neatest in all Great Coramstreet. The area and the area-steps, and the street-door and the street-door steps, and the brass handle, and the door-plate, and the knocker, and the fan-light, were all as clean and bright, as indefatigable white-washing, and hearth-stoning, and scrubbing and rubbing, could make them. The wonder was, that the brass doorplate, with the interesting inscription “MRS. TIBBS,” had never caught fire from constant friction, so perseveringly was it polished. There were meat-safe-looking blinds in the parlourwindows, blue and gold curtains in the drawing-room, and springroller blinds, as Mrs. Tibbs was wont in the pride of her heart to boast, “all the way up.” The bell-lamp in the passage looked as clear as a soap-bubble; you could see yourself in all the tables, and French-polish yourself on any one of the chairs. The banisters were bees-waxed; and the very stair-wires made your eyes wink, they were so glittering.

Mrs. Tibbs was somewhat short of stature, and Mr.

Tibbs was by no means a large man. He had, moreover, very short legs, but, by way of indemnification, his face was peculiarly long. He was to his wife what the 0 is in 90—he was of some importance WITH her—he was nothing without her. Mrs. Tibbs was always talking. Mr. Tibbs rarely spoke; but, if it were at any time possible to put in a word, when he should have said nothing at all, he had that talent. Mrs. Tibbs detested long stories, and Mr. Tibbs had one, the conclusion of which had never been heard by his most intimate friends. It always began, “I recollect when I was in the volunteer corps, in eighteen hundred and six,”—but, as he spoke very slowly and softly, and his better half very quickly and loudly, he rarely got beyond the introductory sentence. He was a melancholy specimen of the story-teller. He was the wandering Jew of Joe Millerism.

Mr. Tibbs enjoyed a small independence from the pension-list—about 43L. 15S. 10D. a year. His father, mother, and five interesting scions from the same stock, drew a like sum from the revenue of a grateful country, though for what particular service was never known. But, as this said independence was not quite sufficient to furnish two people with ALL the luxuries of this life, it had occurred to the busy little spouse of Tibbs, that the best thing she could do with a legacy of 700L., would be to take and furnish a tolerable house—somewhere in that partiallyexplored tract of country which lies between the British Museum, and a remote village called Somers-town—for the reception of boarders. Great Coram-street was the spot pitched upon. The house had been furnished accordingly; two female servants and a boy engaged; and an advertisement inserted in the morning papers, informing the public that “Six individuals would meet with all the comforts of a cheerful musical home in a select private family, residing within ten minutes” walk of”—everywhere. Answers out of number were received, with all sorts of initials; all the letters of the alphabet seemed to be seized with a sudden wish to go out boarding and lodging; voluminous was the correspondence between Mrs. Tibbs and the applicants; and most profound was the secrecy observed. “E.” didn't like this; “ I. ” couldn't think of putting up with that; “I. O. U.” didn't think the terms would suit him; and “G. R.” had never slept in a French bed. The result, however, was, that three gentlemen became inmates of Mrs. Tibbs's house, on terms which were “agreeable to all parties.” In went the advertisement again, and a lady with her two daughters, proposed to increase—not their families, but Mrs. Tibbs's.

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories