- Home

- Charles Dickens

Sketches by Boz Page 48

Sketches by Boz Read online

Page 48

“Lord Peter?” repeated Mr. Trott.

“Oh—ah, I forgot. Mr. Trott, then—Trott—very good, ha! ha!—Well, sir, the chaise shall be ready at half-past twelve.”

“And what is to become of me until then?” inquired Mr. Trott, anxiously. “Wouldn't it save appearances, if I were placed under some restraint?”

“Ah!” replied Overton, “very good thought—capital idea indeed. I'll send somebody up directly. And if you make a little resistance when we put you in the chaise it wouldn't be amiss—look as if you didn't want to be taken away, you know.”

“To be sure,” said Trott—“to be sure.”

“Well, my lord,” said Overton, in a low tone, “until then, I wish your lordship a good evening.”

“Lord—lordship?” ejaculated Trott again, falling back a step or two, and gazing, in unutterable wonder, on the countenance of the mayor.

“Ha-ha! I see, my lord—practising the madman?—very good indeed—very vacant look—capital, my lord, capital—good evening, Mr.—Trott—ha! ha! ha!”

“That mayor's decidedly drunk,” soliloquised Mr. Trott, throwing himself back in his chair, in an attitude of reflection.

“He is a much cleverer fellow than I thought him, that young nobleman—he carries it off uncommonly well,” thought Overton, as he went his way to the bar, there to complete his arrangements. This was soon done. Every word of the story was implicitly believed, and the one-eyed boots was immediately instructed to repair to number nineteen, to act as custodian of the person of the supposed lunatic until half-past twelve o'clock. In pursuance of this direction, that somewhat eccentric gentleman armed himself with a walking-stick of gigantic dimensions, and repaired, with his usual equanimity of manner, to Mr. Trott's apartment, which he entered without any ceremony, and mounted guard in, by quietly depositing himself on a chair near the door, where he proceeded to beguile the time by whistling a popular air with great apparent satisfaction.

“What do you want here, you scoundrel?” exclaimed Mr. Alexander Trott, with a proper appearance of indignation at his detention.

The boots beat time with his head, as he looked gently round at Mr. Trott with a smile of pity, and whistled an ADAGIO movement.

“Do you attend in this room by Mr. Overton's desire?” inquired Trott, rather astonished at the man's demeanour.

“Keep yourself to yourself, young feller,” calmly responded the boots, “and don't say nothing to nobody.” And he whistled again.

“Now mind!” ejaculated Mr. Trott, anxious to keep up the farce of wishing with great earnestness to fight a duel if they'd let him. “I protest against being kept here. I deny that I have any intention of fighting with anybody. But as it's useless contending with superior numbers, I shall sit quietly down.”

“You'd better,” observed the placid boots, shaking the large stick expressively.

“Under protest, however,” added Alexander Trott, seating himself with indignation in his face, but great content in his heart. “Under protest.”

“Oh, certainly!” responded the boots; “anything you please. If you're happy, I'm transported; only don't talk too much—it'll make you worse.”

“Make me worse?” exclaimed Trott, in unfeigned astonishment: “the man's drunk!”

“You'd better be quiet, young feller,” remarked the boots, going through a threatening piece of pantomime with the stick.

“Or mad!” said Mr. Trott, rather alarmed. “Leave the room, sir, and tell them to send somebody else.”

“Won't do!” replied the boots.

“Leave the room!” shouted Trott, ringing the bell violently: for he began to be alarmed on a new score.

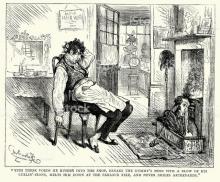

“Leave that “ere bell alone, you wretched loo-nattic!” said the boots, suddenly forcing the unfortunate Trott back into his chair, and brandishing the stick aloft. “Be quiet, you miserable object, and don't let everybody know there's a madman in the house.”

“He IS a madman! He IS a madman!” exclaimed the terrified Mr. Trott, gazing on the one eye of the red-headed boots with a look of abject horror.

“Madman!” replied the boots, “dam'me, I think he IS a madman with a vengeance! Listen to me, you unfortunate. Ah! would you?” [a slight tap on the head with the large stick, as Mr. Trott made another move towards the bell-handle] “I caught you there! did I?”

“Spare my life!” exclaimed Trott, raising his hands imploringly.

“I don't want your life,” replied the boots, disdainfully, “though I think it “ud be a charity if somebody took it.”

“No, no, it wouldn't,” interrupted poor Mr. Trott, hurriedly, “no, no, it wouldn't! I—I-'d rather keep it!”

“O werry well,” said the boots: “that's a mere matter of taste—ev'ry one to his liking. Hows'ever, all I've got to say is this here: You sit quietly down in that chair, and I'll sit hoppersite you here, and if you keep quiet and don't stir, I won't damage you; but, if you move hand or foot till half-past twelve o'clock, I shall alter the expression of your countenance so completely, that the next time you look in the glass you'll ask vether you're gone out of town, and ven you're likely to come back again. So sit down.”

“I will—I will,” responded the victim of mistakes; and down sat Mr. Trott and down sat the boots too, exactly opposite him, with the stick ready for immediate action in case of emergency.

Long and dreary were the hours that followed. The bell of Great Winglebury church had just struck ten, and two hours and a half would probably elapse before succour arrived.

For half an hour, the noise occasioned by shutting up the shops in the street beneath, betokened something like life in the town, and rendered Mr. Trott's situation a little less insupportable; but, when even these ceased, and nothing was heard beyond the occasional rattling of a post-chaise as it drove up the yard to change horses, and then drove away again, or the clattering of horses” hoofs in the stables behind, it became almost unbearable. The boots occasionally moved an inch or two, to knock superfluous bits of wax off the candles, which were burning low, but instantaneously resumed his former position; and as he remembered to have heard, somewhere or other, that the human eye had an unfailing effect in controlling mad people, he kept his solitary organ of vision constantly fixed on Mr. Alexander Trott. That unfortunate individual stared at his companion in his turn, until his features grew more and more indistinct—his hair gradually less red—and the room more misty and obscure. Mr. Alexander Trott fell into a sound sleep, from which he was awakened by a rumbling in the street, and a cry of “Chaise-and-four for number twenty-five!” A bustle on the stairs succeeded; the room door was hastily thrown open; and Mr. Joseph Overton entered, followed by four stout waiters, and Mrs. Williamson, the stout landlady of the Winglebury Arms.

“Mr. Overton!” exclaimed Mr. Alexander Trott, jumping up in a frenzy. “Look at this man, sir; consider the situation in which I have been placed for three hours past—the person you sent to guard me, sir, was a madman—a madman—a raging, ravaging, furious madman.”

“Bravo!” whispered Mr. Overton.

“Poor dear!” said the compassionate Mrs. Williamson, “mad people always thinks other people's mad.”

“Poor dear!” ejaculated Mr. Alexander Trott. “What the devil do you mean by poor dear! Are you the landlady of this house?”

“Yes, yes,” replied the stout old lady, “don't exert yourself, there's a dear! Consider your health, now; do.”

“Exert myself!” shouted Mr. Alexander Trott; “it's a mercy, ma'am, that I have any breath to exert myself with! I might have been assassinated three hours ago by that one-eyed monster with the oakum head. How dare you have a madman, ma'am—how dare you have a madman, to assault and terrify the visitors to your house?”

“I'll never have another,” said Mrs. Williamson, casting a look of reproach at the mayor.

“Capital, capital,” whispered Overton again, as he enveloped Mr. Alexander Trott in a thick travelling-cloak.

“Capital, sir!” excl

aimed Trott, aloud; “it's horrible. The very recollection makes me shudder. I'd rather fight four duels in three hours, if I survived the first three, than I'd sit for that time face to face with a madman.”

“Keep it up, my lord, as you go down-stairs,” whispered Overton, “your bill is paid, and your portmanteau in the chaise.” And then he added aloud, “Now, waiters, the gentleman's ready.”

At this signal, the waiters crowded round Mr. Alexander Trott. One took one arm; another, the other; a third, walked before with a candle; the fourth, behind with another candle; the boots and Mrs. Williamson brought up the rear; and down-stairs they went: Mr. Alexander Trott expressing alternately at the very top of his voice either his feigned reluctance to go, or his unfeigned indignation at being shut up with a madman.

Mr. Overton was waiting at the chaise-door, the boys were ready mounted, and a few ostlers and stable nondescripts were standing round to witness the departure of “the mad gentleman.” Mr. Alexander Trott's foot was on the step, when he observed (which the dim light had prevented his doing before) a figure seated in the chaise, closely muffled up in a cloak like his own.

“Who's that?” he inquired of Overton, in a whisper.

“Hush, hush,” replied the mayor: “the other party of course.”

“The other party!” exclaimed Trott, with an effort to retreat.

“Yes, yes; you'll soon find that out, before you go far, I should think—but make a noise, you'll excite suspicion if you whisper to me so much.”

“I won't go in this chaise!” shouted Mr. Alexander Trott, all his original fears recurring with tenfold violence. “I shall be assassinated—I shall be—”

“Bravo, bravo,” whispered Overton. “I'll push you in.”

“But I won't go,” exclaimed Mr. Trott. “Help here, help! They're carrying me away against my will. This is a plot to murder me.”

“Poor dear!” said Mrs. Williamson again.

“Now, boys, put “em along,” cried the mayor, pushing Trott in and slamming the door. “Off with you, as quick as you can, and stop for nothing till you come to the next stage—all right!”

“Horses are paid, Tom,” screamed Mrs. Williamson; and away went the chaise, at the rate of fourteen miles an hour, with Mr. Alexander Trott and Miss Julia Manners carefully shut up in the inside.

Mr. Alexander Trott remained coiled up in one corner of the chaise, and his mysterious companion in the other, for the first two or three miles; Mr. Trott edging more and more into his corner, as he felt his companion gradually edging more and more from hers; and vainly endeavouring in the darkness to catch a glimpse of the furious face of the supposed Horace Hunter.

“We may speak now,” said his fellow-traveller, at length; “the post-boys can neither see nor hear us.”

“That's not Hunter's voice!”—thought Alexander, astonished.

“Dear Lord Peter!” said Miss Julia, most winningly: putting her arm on Mr. Trott's shoulder. “Dear Lord Peter. Not a word?”

“Why, it's a woman!” exclaimed Mr. Trott, in a low tone of excessive wonder.

“Ah! Whose voice is that?” said Julia; “'tis not Lord Peter's.”

“No,—it's mine,” replied Mr. Trott.

“Yours!” ejaculated Miss Julia Manners; “a strange man! Gracious heaven! How came you here!”

“Whoever you are, you might have known that I came against my will, ma'am,” replied Alexander, “for I made noise enough when I got in.”

“Do you come from Lord Peter?” inquired Miss Manners.

“Confound Lord Peter,” replied Trott pettishly. “I don't know any Lord Peter. I never heard of him before to-night, when I've been Lord Peter'd by one and Lord Peter'd by another, till I verily believe I'm mad, or dreaming—”

“Whither are we going?” inquired the lady tragically.

“How should I know, ma'am?” replied Trott with singular coolness; for the events of the evening had completely hardened him.

“Stop stop!” cried the lady, letting down the front glasses of the chaise.

“Stay, my dear ma'am!” said Mr. Trott, pulling the glasses up again with one hand, and gently squeezing Miss Julia's waist with the other. “There is some mistake here; give me till the end of this stage to explain my share of it. We must go so far; you cannot be set down here alone, at this hour of the night.”

The lady consented; the mistake was mutually explained. Mr. Trott was a young man, had highly promising whiskers, an undeniable tailor, and an insinuating address—he wanted nothing but valour, and who wants that with three thousand a-year? The lady had this, and more; she wanted a young husband, and the only course open to Mr. Trott to retrieve his disgrace was a rich wife. So, they came to the conclusion that it would be a pity to have all this trouble and expense for nothing; and that as they were so far on the road already, they had better go to Gretna Green, and marry each other; and they did so. And the very next preceding entry in the Blacksmith's book, was an entry of the marriage of Emily Brown with Horace Hunter. Mr. Hunter took his wife home, and begged pardon, and WAS pardoned; and Mr. Trott took HIS wife home, begged pardon too, and was pardoned also. And Lord Peter, who had been detained beyond his time by drinking champagne and riding a steeple-chase, went back to the Honourable Augustus Flair's, and drank more champagne, and rode another steeple-chase, and was thrown and killed. And Horace Hunter took great credit to himself for practising on the cowardice of Alexander Trott; and all these circumstances were discovered in time, and carefully noted down; and if you ever stop a week at the Winglebury Arms, they will give you just this account of The Great Winglebury Duel.

CHAPTER IX

MRS. JOSEPH PORTER

Most extensive were the preparations at Rose Villa, Clapham Rise, in the occupation of Mr. Gattleton (a stock-broker in especially comfortable circumstances), and great was the anxiety of Mr. Gattleton's interesting family, as the day fixed for the representation of the Private Play which had been “many months in preparation,” approached. The whole family was infected with the mania for Private Theatricals; the house, usually so clean and tidy, was, to use Mr. Gattleton's expressive description, “regularly turned out o” windows;” the large dining-room, dismantled of its furniture, and ornaments, presented a strange jumble of flats, flies, wings, lamps, bridges, clouds, thunder and lightning, festoons and flowers, daggers and foil, and various other messes in theatrical slang included under the comprehensive name of “properties.” The bedrooms were crowded with scenery, the kitchen was occupied by carpenters. Rehearsals took place every other night in the drawing-room, and every sofa in the house was more or less damaged by the perseverance and spirit with which Mr. Sempronius Gattleton, and Miss Lucina, rehearsed the smothering scene in “Othello”—it having been determined that that tragedy should form the first portion of the evening's entertainments.

“When we're a LEETLE more perfect, I think it will go admirably,” said Mr. Sempronius, addressing his CORPS DRAMATIQUE, at the conclusion of the hundred and fiftieth rehearsal. In consideration of his sustaining the trifling inconvenience of bearing all the expenses of the play, Mr. Sempronius had been, in the most handsome manner, unanimously elected stage-manager. “Evans,” continued Mr. Gattleton, the younger, addressing a tall, thin, pale young gentleman, with extensive whiskers—“Evans, you play RODERIGO beautifully.”

“Beautifully,” echoed the three Miss Gattletons; for Mr. Evans was pronounced by all his lady friends to be “quite a dear.” He looked so interesting, and had such lovely whiskers: to say nothing of his talent for writing verses in albums and playing the flute! RODERIGO simpered and bowed.

“But I think,” added the manager, “you are hardly perfect in the—fall—in the fencing-scene, where you are—you understand?”

“It's very difficult,” said Mr. Evans, thoughtfully; “I've fallen about, a good deal, in our counting-house lately, for practice, only I find it hurts one so. Being obliged to fall backward you see, it bruises one's head a good deal.”

>

“But you must take care you don't knock a wing down,” said Mr. Gattleton, the elder, who had been appointed prompter, and who took as much interest in the play as the youngest of the company. “The stage is very narrow, you know.”

“Oh! don't be afraid,” said Mr. Evans, with a very self-satisfied air; “I shall fall with my head “off,” and then I can't do any harm.”

“But, egad,” said the manager, rubbing his hands, “we shall make a decided hit in “Masaniello.” Harleigh sings that music admirably.”

Everybody echoed the sentiment. Mr. Harleigh smiled, and looked foolish—not an unusual thing with him—hummed” Behold how brightly breaks the morning,” and blushed as red as the fisherman's nightcap he was trying on.

“Let's see,” resumed the manager, telling the number on his fingers, “we shall have three dancing female peasants, besides FENELLA, and four fishermen. Then, there's our man Tom; he can have a pair of ducks of mine, and a check shirt of Bob's, and a red nightcap, and he'll do for another—that's five. In the choruses, of course, we can sing at the sides; and in the market-scene we can walk about in cloaks and things. When the revolt takes place, Tom must keep rushing in on one side and out on the other, with a pickaxe, as fast as he can. The effect will be electrical; it will look exactly as if there were an immense number of “em. And in the eruption-scene we must burn the red fire, and upset the tea-trays, and make all sorts of noises—and it's sure to do.”

“Sure! sure!” cried all the performers UNA VOCE—and away hurried Mr. Sempronius Gattleton to wash the burnt cork off his face, and superintend the “setting up” of some of the amateur-painted, but never-sufficiently-to-be-admired, scenery.

Mrs. Gattleton was a kind, good-tempered, vulgar soul, exceedingly fond of her husband and children, and entertaining only three dislikes. In the first place, she had a natural antipathy to anybody else's unmarried daughters; in the second, she was in bodily fear of anything in the shape of ridicule; lastly—almost a necessary consequence of this feeling—she regarded, with feelings of the utmost horror, one Mrs. Joseph Porter over the way. However, the good folks of Clapham and its vicinity stood very much in awe of scandal and sarcasm; and thus Mrs. Joseph Porter was courted, and flattered, and caressed, and invited, for much the same reason that induces a poor author, without a farthing in his pocket, to behave with extraordinary civility to a twopenny postman.

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories