- Home

- Charles Dickens

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Page 5

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Read online

Page 5

CHAPTER III

_A New Acquaintance. The Stroller's Tale. A Disagreeable Interruption, and an Unpleasant Encounter_

Mr. Pickwick had felt some apprehensions in consequence of the unusualabsence of his two friends, which their mysterious behaviour during thewhole morning had by no means tended to diminish. It was, therefore,with more than ordinary pleasure that he rose to greet them when theyagain entered; and with more than ordinary interest that he inquiredwhat had occurred to detain them from his society. In reply to hisquestions on this point, Mr. Snodgrass was about to offer an historicalaccount of the circumstances just now detailed, when he was suddenlychecked by observing that there were present, not only Mr. Tupmanand their stage-coach companion of the preceding day, but anotherstranger of equally singular appearance. It was a care-worn lookingman, whose sallow face, and deeply sunken eyes, were rendered stillmore striking than nature had made them, by the straight black hairwhich hung in matted disorder half way down his face. His eyes werealmost unnaturally bright and piercing; his cheek-bones were high andprominent; and his jaws were so long and lank, that an observer wouldhave supposed that he was drawing the flesh of his face in, for amoment, by some contraction of the muscles, if his half-opened mouthand immovable expression had not announced that it was his ordinaryappearance. Round his neck he wore a green shawl, with the large endsstraggling over his chest, and making their appearance occasionallybeneath the worn buttonholes of his old waistcoat. His upper garmentwas a long black surtout; and below it he wore wide drab trousers, andlarge boots, running rapidly to seed.

It was on this uncouth-looking person that Mr. Winkle's eye rested, andit was towards him that Mr. Pickwick extended his hand, when he said,"A friend of our friend's here. We discovered this morning that ourfriend was connected with the theatre in this place, though he is notdesirous to have it generally known, and this gentleman is a member ofthe same profession. He was about to favour us with a little anecdoteconnected with it when you entered."

"Lots of anecdote," said the green-coated stranger of the day before,advancing to Mr. Winkle and speaking in a low and confidential tone."Rum fellow--does the heavy business--no actor--strange man--all sortsof miseries--Dismal Jemmy we call him on the circuit." Mr. Winkle andMr. Snodgrass politely welcomed the gentleman, elegantly designated as"Dismal Jemmy!" and calling for brandy and water, in imitation of theremainder of the company, seated themselves at the table.

"Now, sir," said Mr. Pickwick, "will you oblige us by proceeding withwhat you were going to relate?"

The dismal individual took a dirty roll of paper from his pocket, andturning to Mr. Snodgrass, who had just taken out his note-book, said ina hollow voice, perfectly in keeping with his outward man--"Are you thepoet?"

"I--I do a little in that way," replied Mr. Snodgrass, rather takenaback by the abruptness of the question.

"Ah! poetry makes life what lights and music do the stage--strip theone of its false embellishments, and the other of its illusions, andwhat is there real in either to live or care for?"

"Very true, sir," replied Mr. Snodgrass.

"To be before the footlights," continued the dismal man, "is likesitting at a grand court show, and admiring the silken dresses of thegaudy throng--to be behind them is to be the people who make thatfinery, uncared for and unknown, and left to sink or swim, to starve orlive, as fortune wills it."

"Certainly," said Mr. Snodgrass: for the sunken eye of the dismal manrested on him, and he felt it necessary to say something.

"Go on, Jemmy," said the Spanish traveller, "like black-eyed Susan--allin the Downs--no croaking--speak out--look lively."

"Will you make another glass before you begin, sir?" said Mr. Pickwick.

The dismal man took the hint, and having mixed a glass of brandy andwater, and slowly swallowed half of it, opened the roll of paper,and proceeded, partly to read, and partly to relate, the followingincident, which we find recorded on the Transactions of the club as"The Stroller's Tale."

THE STROLLER'S TALE

"There is nothing of the marvellous in what I am going to relate,"said the dismal man; "there is nothing even uncommon in it. Want andsickness are too common in many stations of life, to deserve morenotice than is usually bestowed on the most ordinary vicissitudes ofhuman nature. I have thrown these few notes together, because thesubject of them was well known to me for many years. I traced hisprogress downwards, step by step, until at last he reached that excessof destitution from which he never rose again.

"The man of whom I speak was a low pantomime actor; and like manypeople of his class, an habitual drunkard. In his better days, beforehe had become enfeebled by dissipation and emaciated by disease, he hadbeen in the receipt of a good salary, which, if he had been carefuland prudent, he might have continued to receive for some years--notmany; because these men either die early, or, by unnaturally taxingtheir bodily energies, lose, prematurely, those physical powers onwhich alone they can depend for subsistence. His besetting sin gainedso fast upon him, however, that it was found impossible to employ himin the situations in which he really was useful to the theatre. Thepublic-house had a fascination for him which he could not resist.Neglected disease and hopeless poverty were as certain to be hisportion as death itself, if he persevered in the same course; yet he_did_ persevere, and the result may be guessed. He could obtain noengagement, and he wanted bread.

"Everybody who is at all acquainted with theatrical matters knowswhat a host of shabby, poverty-stricken men hang about the stage of alarge establishment--not regularly engaged actors, but ballet people,procession men, tumblers, and so forth, who are taken on during the runof a pantomime, or an Easter piece, and are then discharged, until theproduction of some heavy spectacle occasions a new demand for theirservices. To this mode of life the man was compelled to resort; andtaking the chair every night at some low theatrical house, at onceput him in possession of a few more shillings weekly, and enabled himto gratify his old propensity. Even this resource shortly failed him;his irregularities were too great to admit of his earning the wretchedpittance he might thus have procured, and he was actually reduced to astate bordering on starvation, only procuring a trifle occasionally byborrowing it of some old companion, or by obtaining an appearance atone or other of the commonest of the minor theatres; and when he didearn anything it was spent in the old way.

"About this time, and when he had been existing for upwards of a yearno one knew how, I had a short engagement at one of the theatres onthe Surrey side of the water, and here I saw this man whom I had lostsight of for some time; for I had been travelling in the provinces, andhe had been skulking in the lanes and alleys of London. I was dressedto leave the house, and was crossing the stage on my way out, when hetapped me on the shoulder. Never shall I forget the repulsive sightthat met my eye when I turned round. He was dressed for the pantomime,in all the absurdity of a clown's costume. The spectral figures in theDance of Death, the most frightful shapes that the ablest painter everportrayed on canvas, never presented an appearance half so ghastly. Hisbloated body and shrunken legs--their deformity enhanced a hundred foldby the fantastic dress--the glassy eyes, contrasting fearfully with thethick white paint with which the face was besmeared; the grotesquelyornamented head, trembling with paralysis, and the long skinnyhands, rubbed with white chalk--all gave him a hideous and unnaturalappearance, of which no description could convey an adequate idea,and which, to this day, I shudder to think of. His voice was hollowand tremulous, as he took me aside, and in broken words recounted along catalogue of sickness and privations, terminating as usual withan urgent request for the loan of a trifling sum of money. I put afew shillings in his hand, and as I turned away I heard the roar oflaughter which followed his first tumble on the stage.

"A few nights afterwards, a boy put a dirty scrap of paper in my hand,on which were scrawled a few words in pencil, intimating that the manwas dangerously ill, and begging me, after the performance, to see himat his lodging in some street--I forget the name o

f it now--at no greatdistance from the theatre. I promised to comply, as soon as I couldget away; and, after the curtain fell, sallied forth on my melancholyerrand.

"It was late, for I had been playing in the last piece; and as it wasa benefit night, the performances had been protracted to an unusuallength. It was a dark cold night, with a chill damp wind, which blewthe rain heavily against the windows and house fronts. Pools of waterhad collected in the narrow and little-frequented streets, and as manyof the thinly-scattered oil-lamps had been blown out by the violenceof the wind, the walk was not only a comfortless, but most uncertainone. I had fortunately taken the right course, however, and succeeded,after a little difficulty, in finding the house to which I had beendirected--a coal-shed, with one storey above it, in the back room ofwhich lay the object of my search.

"A wretched-looking woman, the man's wife, met me on the stairs, and,telling me that he had just fallen into a kind of doze, led me softlyin, and placed a chair for me at the bedside. The sick man was lyingwith his face turned towards the wall; and as he took no heed of mypresence, I had leisure to observe the place in which I found myself.

"He was lying on an old bedstead, which turned up during the day. Thetattered remains of a checked curtain were drawn round the bed's head,to exclude the wind, which however made its way into the comfortlessroom through the numerous chinks in the door, and blew it to and froevery instant. There was a low cinder fire in a rusty unfixed grate;and an old three-cornered stained table, with some medicine bottles, abroken glass, and a few other domestic articles, was drawn out beforeit. A little child was sleeping on a temporary bed which had been madefor it on the floor, and the woman sat on a chair by its side. Therewere a couple of shelves, with a few plates and cups and saucers: anda pair of stage shoes and a couple of foils hung beneath them. With theexception of little heaps of rags and bundles which had been carelesslythrown into the corners of the room, these were the only things in theapartment.

"I had had time to note these little particulars, and to mark theheavy breathing and feverish startings of the sick man, before he wasaware of my presence. In the restless attempts to procure some easyresting-place for his head, he tossed his hand out of the bed, and itfell on mine. He started up, and stared eagerly in my face.

"'Mr. Hutley, John,' said his wife; 'Mr. Hutley, that you sent forto-night, you know.'

"'Ah!' said the invalid, passing his hand across his forehead;'Hutley--Hutley--let me see.' He seemed endeavouring to collect histhoughts for a few seconds, and then grasping me tightly by the wristsaid, 'Don't leave me--don't leave me, old fellow. She'll murder me; Iknow she will.'

"'Has he been long so?' said I, addressing his weeping wife.

"'Since yesterday night,' she replied. 'John, John, don't you know me?'

"'Don't let her come near me,' said the man, with a shudder, as shestooped over him. 'Drive her away; I can't bear her near me.' He staredwildly at her with a look of deadly apprehension, and then whispered inmy ear, 'I beat her, Jem; I beat her yesterday, and many times before.I have starved her and the boy too; and now I am weak and helpless,Jem, she'll murder me for it; I know she will. If you'd seen her cry,as I have, you'd know it too. Keep her off.' He relaxed his grasp, andsank back exhausted on the pillow.

"I knew but too well what all this meant. If I could have entertainedany doubt of it, for an instant, one glance at the woman's pale faceand wasted form would have sufficiently explained the real state of thecase. 'You had better stand aside,' said I to the poor creature. 'Youcan do him no good. Perhaps he will be calmer, if he does not see you.'She retired out of the man's sight. He opened his eyes after a fewseconds, and looked anxiously round.

"'Is she gone?' he eagerly inquired.

"'Yes--yes,' said I; 'she shall not hurt you.'

"'I'll tell you what, Jem,' said the man, in a low voice, 'she _does_hurt me. There's something in her eyes wakes such a dreadful fear inmy heart that it drives me mad. All last night her large staring eyesand pale face were close to mine; wherever I turned, they turned: andwhenever I started up from my sleep, she was at the bedside lookingat me.' He drew me closer to him, as he said in a deep, alarmedwhisper--'Jem, she must be an evil spirit--a devil! Hush! I know sheis. If she had been a woman she would have died long ago. No womancould have borne what she has.'

"I sickened at the thought of the long course of cruelty and neglectwhich must have occurred to produce such an impression on such a man. Icould say nothing in reply; for who could offer hope, or consolation,to the abject being before me?

"I sat there for upwards of two hours, during which he tossed about,murmuring exclamations of pain or impatience, restlessly throwing hisarms here and there, and turning constantly from side to side. Atlength he fell into that state of partial unconsciousness, in which themind wanders uneasily from scene to scene, and from place to place,without the control of reason, but still without being able to divestitself of an indescribable sense of present suffering. Finding from hisincoherent wanderings that this was the case, and knowing that in allprobability the fever would not grow immediately worse, I left him,promising his miserable wife that I would repeat my visit next evening,and, if necessary, sit up with the patient during the night.

"I kept my promise. The last four-and-twenty hours had produced afrightful alteration. The eyes, though deeply sunk and heavy, shonewith a lustre frightful to behold. The lips were parched, and crackedin many places: the hard dry skin glowed with a burning heat, andthere was an almost unearthly air of wild anxiety in the man's face,indicating even more strongly the ravages of the disease. The fever wasat its height.

"I took the seat I had occupied the night before, and there I sat forhours, listening to sounds which must strike deep to the heart of themost callous among human beings--the awful ravings of a dying man.From what I had heard of the medical attendant's opinion, I knew therewas no hope for him: I was sitting by his death-bed. I saw the wastedlimbs, which a few hours before had been distorted for the amusement ofa boisterous gallery, writhing under the tortures of a burning fever--Iheard the clown's shrill laugh, blending with the low murmurings of thedying man.

"It is a touching thing to hear the mind reverting to the ordinaryoccupations and pursuits of health, when the body lies before youweak and helpless; but when those occupations are of a character themost strongly opposed to anything we associate with grave and solemnideas, the impression produced is infinitely more powerful. The theatreand the public-house were the chief themes of the wretched man'swanderings. It was evening, he fancied; he had a part to play thatnight; it was late, and he must leave home instantly. Why did they holdhim, and prevent his going?--he should lose the money--he must go.No! they would not let him. He hid his face in his burning hands, andfeebly bemoaned his own weakness, and the cruelty of his persecutors. Ashort pause, and he shouted out a few doggrel rhymes--the last he hadever learnt. He rose in bed, drew up his withered limbs, and rolledabout in uncouth positions; he was acting--he was at the theatre. Aminute's silence, and he murmured the burden of some roaring song. Hehad reached the old house at last: how hot the room was. He had beenill, very ill, but he was well now, and happy. Fill up his glass. Whowas that, that dashed it from his lips? It was the same persecutor thathad followed him before. He fell back upon his pillow and moaned aloud.A short period of oblivion, and he was wandering through a tediousmaze of low-arched rooms--so low sometimes, that he must creep uponhis hands and knees to make his way along; it was so close and dark,and every way he turned, some obstacle impeded his progress. Therewere insects too, hideous crawling things with eyes that stared uponhim, and filled the very air around; glistening horribly amidst thethick darkness of the place. The walls and ceiling were alive withreptiles--the vault expanded to an enormous size--frightful figuresflitted to and fro--and the faces of men he knew, rendered hideous bygibing and mouthing, peered out from among them; they were searinghim with heated irons, and binding his head with cords till the bloodstarted; and he struggled madly for life.

* * * * *

It would afford us the highest gratification to be enabled to recordMr. Pickwick's opinion of the foregoing anecdote. We have little doubtthat we should have been enabled to present it to our readers, but fora most unfortunate occurrence.

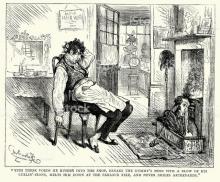

Mr. Pickwick had replaced on the table the glass which, during thelast few sentences of the tale, he had retained in his hand; and hadjust made up his mind to speak--indeed, we have the authority of Mr.Snodgrass's note-book for stating, that he had actually opened hismouth--when the waiter entered the room, and said--

"Some gentlemen, sir."

It has been conjectured that Mr. Pickwick was on the point ofdelivering some remarks which would have enlightened the world, if notthe Thames, when he was thus interrupted; for he gazed sternly on thewaiter's countenance, and then looked round on the company generally,as if seeking for information relative to the new comers.

"Oh!" said Mr. Winkle, rising, "some friends of mine--show themin. Very pleasant fellows," added Mr. Winkle, after the waiter hadretired--"Officers of the 97th, whose acquaintance I made rather oddlythis morning. You will like them very much."

Mr. Pickwick's equanimity was at once restored. The waiter returned,and ushered three gentlemen into the room.

"Lieutenant Tappleton," said Mr. Winkle, "Lieutenant Tappleton,Mr. Pickwick--Doctor Payne, Mr. Pickwick--Mr. Snodgrass, you haveseen before; my friend Mr. Tupman, Doctor Payne--Dr. Slammer, Mr.Pickwick--Mr. Tupman, Doctor Slam--"

Here Mr. Winkle suddenly paused; for strong emotion was visible on thecountenance of Mr. Tupman and the Doctor.

"I have met _this_ gentleman before," said the Doctor, with markedemphasis.

"Indeed!" said Mr. Winkle.

"And--and that person too, if I am not mistaken," said the Doctor,bestowing a scrutinising glance on the green-coated stranger. "Ithink I gave that person a very pressing invitation last night,which he thought proper to decline." Saying which the Doctor scowledmagnanimously on the stranger, and whispered his friend LieutenantTappleton.

"You don't say so," said that gentleman, at the conclusion of thewhisper.

"I do, indeed," replied Dr. Slammer.

"You are bound to kick him on the spot," murmured the owner of thecamp-stool with great importance.

"_Do_ be quiet, Payne," interposed the Lieutenant. "Will you allowme to ask you, sir," he said, addressing Mr. Pickwick, who wasconsiderably mystified by this very unpolite by-play, "will you allowme to ask you, sir, whether that person belongs to your party?"

"No, sir," replied Mr. Pickwick, "he is a guest of ours."

"He is a member of your club, or I am mistaken?" said the Lieutenant,inquiringly.

"Certainly not," responded Mr. Pickwick.

"And never wears your club-button?" said the Lieutenant.

"No--never!" replied the astonished Mr. Pickwick.

Lieutenant Tappleton turned round to his friend Dr. Slammer, with ascarcely perceptible shrug of the shoulder, as if implying some doubtof the accuracy of his recollection. The little Doctor looked wrathful,but confounded; and Mr. Payne gazed with a ferocious aspect on thebeaming countenance of the unconscious Pickwick.

"Sir," said the Doctor, suddenly addressing Mr. Tupman, in a tone whichmade that gentleman start as perceptibly as if a pin had been cunninglyinserted in the calf of his leg, "you were at the ball here last night!"

Mr. Tupman gasped a faint affirmative, looking very hard at Mr.Pickwick all the while.

"That person was your companion," said the Doctor, pointing to thestill unmoved stranger.

Mr. Tupman admitted the fact.

"Now, sir," said the Doctor to the stranger, "I ask you once again, inthe presence of these gentlemen, whether you choose to give me yourcard, and to receive the treatment of a gentleman; or whether youimpose upon me the necessity of personally chastising you on the spot?"

"Stay, sir," said Mr. Pickwick, "I really cannot allow this matterto go any further without some explanation. Tupman, recount thecircumstances."

Mr. Tupman, thus solemnly adjured, stated the case in a few words;touched slightly on the borrowing of the coat; expatiated largely onits having been done "after dinner;" wound up with a little penitenceon his own account; and left the stranger to clear himself as best hecould.

He was apparently about to proceed to do so, when Lieutenant Tappleton,who had been eyeing him with great curiosity, said with considerablescorn--"Haven't I seen you at the theatre, sir?"

"Certainly," replied the unabashed stranger.

"He is a strolling actor!" said the Lieutenant, contemptuously; turningto Dr. Slammer--"He acts in the piece that the Officers of the 52nd getup at the Rochester Theatre to-morrow night. You cannot proceed in thisaffair, Slammer--impossible!"

"Sorry to have placed you in this disagreeable situation," saidLieutenant Tappleton, addressing Mr. Pickwick; "allow me to suggest,that the best way of avoiding a recurrence of such scenes in future,will be to be more select in the choice of your companions. Goodevening, sir!" and the Lieutenant bounced out of the room.

"And allow _me_ to say, sir," said the irascible Doctor Payne, "thatif I had been Tappleton, or if I had been Slammer, I would have pulledyour nose, sir, and the nose of every man in this company. I would,sir, every man. Payne is my name, sir--Doctor Payne of the 43rd. Goodevening, sir." Having concluded this speech, and uttered the three lastwords in a loud key, he stalked majestically after his friend, closelyfollowed by Doctor Slammer, who said nothing, but contented himself bywithering the company with a look.

Rising rage and extreme bewilderment had swelled the noble breast ofMr. Pickwick, almost to the bursting of his waistcoat, during thedelivery of the above defiance. He stood transfixed to the spot, gazingon vacancy. The closing of the door recalled him to himself. He rushedforward with fury in his looks, and fire in his eye. His hand was uponthe lock of the door; in another instant it would have been on thethroat of Doctor Payne of the 43rd, had not Mr. Snodgrass seized hisrevered leader by the coat-tail, and dragged him backwards.

"Restrain him," cried Mr. Snodgrass. "Winkle, Tupman--he must not perilhis distinguished life in such a cause as this."

"Let me go," said Mr. Pickwick.

"Hold him tight," shouted Mr. Snodgrass; and by the united efforts ofthe whole company, Mr. Pickwick was forced into an arm-chair.

"Leave him alone," said the green-coated stranger--"brandy andwater--jolly old gentleman--lots of pluck--swallow this--ah!--capitalstuff." Having previously tested the virtues of a bumper, which hadbeen mixed by the dismal man, the stranger applied the glass to Mr.Pickwick's mouth; and the remainder of its contents rapidly disappeared.

There was a short pause; the brandy and water had done its work; theamiable countenance of Mr. Pickwick was fast recovering its customaryexpression.

"They are not worth your notice," said the dismal man.

"You are right, sir," replied Mr. Pickwick, "they are not. I am ashamedto have been betrayed into this warmth of feeling. Draw your chair upto the table,

sir."

The dismal man readily complied: a circle was again formed round thetable, and harmony once more prevailed. Some lingering irritabilityappeared to find a resting-place in Mr. Winkle's bosom, occasionedpossibly by the temporary abstraction of his coat--though it isscarcely reasonable to suppose that so slight a circumstance can haveexcited even a passing feeling of anger in a Pickwickian breast. Withthis exception, their good humour was completely restored; and theevening concluded with the conviviality with which it had begun.

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories