- Home

- Charles Dickens

The Battle of Life Page 6

The Battle of Life Read online

Page 6

It was a busy day for all of them: a busier day for none of them than Grace, who noiselessly presided everywhere, and was the cheerful mind of all the preparations. Many a time that day (as well as many a time within the fleeting month preceding it), did Clemency glance anxiously, and almost fearfully, at Marion. She saw her paler, perhaps, than usual; but there was a sweet composure on her face that made it lovelier than ever.

At night when she was dressed, and wore upon her head a wreath that Grace had proudly twined about it - its mimic flowers were Alfred's favourites, as Grace remembered when she chose them - that old expression, pensive, almost sorrowful, and yet so spiritual, high, and stirring, sat again upon her brow, enhanced a hundred-fold.

'The next wreath I adjust on this fair head, will be a marriage wreath,' said Grace; 'or I am no true prophet, dear.'

Her sister smiled, and held her in her arms.

'A moment, Grace. Don't leave me yet. Are you sure that I want nothing more?'

Her care was not for that. It was her sister's face she thought of, and her eyes were fixed upon it, tenderly.

'My art,' said Grace, 'can go no farther, dear girl; nor your beauty. I never saw you look so beautiful as now.'

'I never was so happy,' she returned.

'Ay, but there is a greater happiness in store. In such another home, as cheerful and as bright as this looks now,' said Grace, 'Alfred and his young wife will soon be living.'

She smiled again. 'It is a happy home, Grace, in your fancy. I can see it in your eyes. I know it WILL be happy, dear. How glad I am to know it.'

'Well,' cried the Doctor, bustling in. 'Here we are, all ready for Alfred, eh? He can't be here until pretty late - an hour or so before midnight - so there'll be plenty of time for making merry before he comes. He'll not find us with the ice unbroken. Pile up the fire here, Britain! Let it shine upon the holly till it winks again. It's a world of nonsense, Puss; true lovers and all the rest of it - all nonsense; but we'll be nonsensical with the rest of 'em, and give our true lover a mad welcome. Upon my word!' said the old Doctor, looking at his daughters proudly, 'I'm not clear to-night, among other absurdities, but that I'm the father of two handsome girls.'

'All that one of them has ever done, or may do - may do, dearest father - to cause you pain or grief, forgive her,' said Marion, 'forgive her now, when her heart is full. Say that you forgive her. That you will forgive her. That she shall always share your love, and -,' and the rest was not said, for her face was hidden on the old man's shoulder.

'Tut, tut, tut,' said the Doctor gently. 'Forgive! What have I to forgive? Heyday, if our true lovers come back to flurry us like this, we must hold 'em at a distance; we must send expresses out to stop 'em short upon the road, and bring 'em on a mile or two a day, until we're properly prepared to meet 'em. Kiss me, Puss. Forgive! Why, what a silly child you are! If you had vexed and crossed me fifty times a day, instead of not at all, I'd forgive you everything, but such a supplication. Kiss me again, Puss. There! Prospective and retrospective - a clear score between us. Pile up the fire here! Would you freeze the people on this bleak December night! Let us be light, and warm, and merry, or I'll not forgive some of you!'

So gaily the old Doctor carried it! And the fire was piled up, and the lights were bright, and company arrived, and a murmuring of lively tongues began, and already there was a pleasant air of cheerful excitement stirring through all the house.

More and more company came flocking in. Bright eyes sparkled upon Marion; smiling lips gave her joy of his return; sage mothers fanned themselves, and hoped she mightn't be too youthful and inconstant for the quiet round of home; impetuous fathers fell into disgrace for too much exaltation of her beauty; daughters envied her; sons envied him; innumerable pairs of lovers profited by the occasion; all were interested, animated, and expectant.

Mr. and Mrs. Craggs came arm in arm, but Mrs. Snitchey came alone. 'Why, what's become of HIM?' inquired the Doctor.

The feather of a Bird of Paradise in Mrs. Snitchey's turban, trembled as if the Bird of Paradise were alive again, when she said that doubtless Mr. Craggs knew. SHE was never told.

'That nasty office,' said Mrs. Craggs.

'I wish it was burnt down,' said Mrs. Snitchey.

'He's - he's - there's a little matter of business that keeps my partner rather late,' said Mr. Craggs, looking uneasily about him.

'Oh-h! Business. Don't tell me!' said Mrs. Snitchey.

'WE know what business means,' said Mrs. Craggs.

But their not knowing what it meant, was perhaps the reason why Mrs. Snitchey's Bird of Paradise feather quivered so portentously, and why all the pendant bits on Mrs. Craggs's ear-rings shook like little bells.

'I wonder YOU could come away, Mr. Craggs,' said his wife.

'Mr. Craggs is fortunate, I'm sure!' said Mrs. Snitchey.

'That office so engrosses 'em,' said Mrs. Craggs.

'A person with an office has no business to be married at all,' said Mrs. Snitchey.

Then, Mrs. Snitchey said, within herself, that that look of hers had pierced to Craggs's soul, and he knew it; and Mrs. Craggs observed to Craggs, that 'his Snitcheys' were deceiving him behind his back, and he would find it out when it was too late.

Still, Mr. Craggs, without much heeding these remarks, looked uneasily about until his eye rested on Grace, to whom he immediately presented himself.

'Good evening, ma'am,' said Craggs. 'You look charmingly. Your - Miss - your sister, Miss Marion, is she - '

'Oh, she's quite well, Mr. Craggs.'

'Yes - I - is she here?' asked Craggs.

'Here! Don't you see her yonder? Going to dance?' said Grace.

Mr. Craggs put on his spectacles to see the better; looked at her through them, for some time; coughed; and put them, with an air of satisfaction, in their sheath again, and in his pocket.

Now the music struck up, and the dance commenced. The bright fire crackled and sparkled, rose and fell, as though it joined the dance itself, in right good fellowship. Sometimes, it roared as if it would make music too. Sometimes, it flashed and beamed as if it were the eye of the old room: it winked too, sometimes, like a knowing patriarch, upon the youthful whisperers in corners. Sometimes, it sported with the holly-boughs; and, shining on the leaves by fits and starts, made them look as if they were in the cold winter night again, and fluttering in the wind. Sometimes its genial humour grew obstreperous, and passed all bounds; and then it cast into the room, among the twinkling feet, with a loud burst, a shower of harmless little sparks, and in its exultation leaped and bounded, like a mad thing, up the broad old chimney.

Another dance was near its close, when Mr. Snitchey touched his partner, who was looking on, upon the arm.

Mr. Craggs started, as if his familiar had been a spectre.

'Is he gone?' he asked.

'Hush! He has been with me,' said Snitchey, 'for three hours and more. He went over everything. He looked into all our arrangements for him, and was very particular indeed. He - Humph!'

The dance was finished. Marion passed close before him, as he spoke. She did not observe him, or his partner; but, looked over her shoulder towards her sister in the distance, as she slowly made her way into the crowd, and passed out of their view.

'You see! All safe and well,' said Mr. Craggs. 'He didn't recur to that subject, I suppose?'

'Not a word.'

'And is he really gone? Is he safe away?'

'He keeps to his word. He drops down the river with the tide in that shell of a boat of his, and so goes out to sea on this dark night! - a dare-devil he is - before the wind. There's no such lonely road anywhere else. That's one thing. The tide flows, he says, an hour before midnight - about this time. I'm glad it's over.' Mr. Snitchey wiped his forehead, which looked hot and anxious.

'What do you think,' said Mr. Craggs, 'about - '

'Hush!' replied his cautious partner, looking straight before him. 'I understand you. Don't mention names, and don't let us, seem

to be talking secrets. I don't know what to think; and to tell you the truth, I don't care now. It's a great relief. His self-love deceived him, I suppose. Perhaps the young lady coquetted a little. The evidence would seem to point that way. Alfred not arrived?'

'Not yet,' said Mr. Craggs. 'Expected every minute.'

'Good.' Mr. Snitchey wiped his forehead again. 'It's a great relief. I haven't been so nervous since we've been in partnership. I intend to spend the evening now, Mr. Craggs.'

Mrs. Craggs and Mrs. Snitchey joined them as he announced this intention. The Bird of Paradise was in a state of extreme vibration, and the little bells were ringing quite audibly.

'It has been the theme of general comment, Mr. Snitchey,' said Mrs. Snitchey. 'I hope the office is satisfied.'

'Satisfied with what, my dear?' asked Mr. Snitchey.

'With the exposure of a defenceless woman to ridicule and remark,' returned his wife. 'That is quite in the way of the office, THAT is.'

'I really, myself,' said Mrs. Craggs, 'have been so long accustomed to connect the office with everything opposed to domesticity, that I am glad to know it as the avowed enemy of my peace. There is something honest in that, at all events.'

'My dear,' urged Mr. Craggs, 'your good opinion is invaluable, but I never avowed that the office was the enemy of your peace.'

'No,' said Mrs. Craggs, ringing a perfect peal upon the little bells. 'Not you, indeed. You wouldn't be worthy of the office, if you had the candour to.'

'As to my having been away to-night, my dear,' said Mr. Snitchey, giving her his arm, 'the deprivation has been mine, I'm sure; but, as Mr. Craggs knows - '

Mrs. Snitchey cut this reference very short by hitching her husband to a distance, and asking him to look at that man. To do her the favour to look at him!

'At which man, my dear?' said Mr. Snitchey.

'Your chosen companion; I'M no companion to you, Mr. Snitchey.'

'Yes, yes, you are, my dear,' he interposed.

'No, no, I'm not,' said Mrs. Snitchey with a majestic smile. 'I know my station. Will you look at your chosen companion, Mr. Snitchey; at your referee, at the keeper of your secrets, at the man you trust; at your other self, in short?'

The habitual association of Self with Craggs, occasioned Mr. Snitchey to look in that direction.

'If you can look that man in the eye this night,' said Mrs. Snitchey, 'and not know that you are deluded, practised upon, made the victim of his arts, and bent down prostrate to his will by some unaccountable fascination which it is impossible to explain and against which no warning of mine is of the least avail, all I can say is - I pity you!'

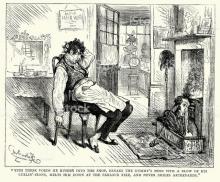

At the very same moment Mrs. Craggs was oracular on the cross subject. Was it possible, she said, that Craggs could so blind himself to his Snitcheys, as not to feel his true position? Did he mean to say that he had seen his Snitcheys come into that room, and didn't plainly see that there was reservation, cunning, treachery, in the man? Would he tell her that his very action, when he wiped his forehead and looked so stealthily about him, didn't show that there was something weighing on the conscience of his precious Snitcheys (if he had a conscience), that wouldn't bear the light? Did anybody but his Snitcheys come to festive entertainments like a burglar? - which, by the way, was hardly a clear illustration of the case, as he had walked in very mildly at the door. And would he still assert to her at noon-day (it being nearly midnight), that his Snitcheys were to be justified through thick and thin, against all facts, and reason, and experience?

Neither Snitchey nor Craggs openly attempted to stem the current which had thus set in, but, both were content to be carried gently along it, until its force abated. This happened at about the same time as a general movement for a country dance; when Mr. Snitchey proposed himself as a partner to Mrs. Craggs, and Mr. Craggs gallantly offered himself to Mrs. Snitchey; and after some such slight evasions as 'why don't you ask somebody else?' and 'you'll be glad, I know, if I decline,' and 'I wonder you can dance out of the office' (but this jocosely now), each lady graciously accepted, and took her place.

It was an old custom among them, indeed, to do so, and to pair off, in like manner, at dinners and suppers; for they were excellent friends, and on a footing of easy familiarity. Perhaps the false Craggs and the wicked Snitchey were a recognised fiction with the two wives, as Doe and Roe, incessantly running up and down bailiwicks, were with the two husbands: or, perhaps the ladies had instituted, and taken upon themselves, these two shares in the business, rather than be left out of it altogether. But, certain it is, that each wife went as gravely and steadily to work in her vocation as her husband did in his, and would have considered it almost impossible for the Firm to maintain a successful and respectable existence, without her laudable exertions.

But, now, the Bird of Paradise was seen to flutter down the middle; and the little bells began to bounce and jingle in poussette; and the Doctor's rosy face spun round and round, like an expressive pegtop highly varnished; and breathless Mr. Craggs began to doubt already, whether country dancing had been made 'too easy,' like the rest of life; and Mr. Snitchey, with his nimble cuts and capers, footed it for Self and Craggs, and half-a-dozen more.

Now, too, the fire took fresh courage, favoured by the lively wind the dance awakened, and burnt clear and high. It was the Genius of the room, and present everywhere. It shone in people's eyes, it sparkled in the jewels on the snowy necks of girls, it twinkled at their ears as if it whispered to them slyly, it flashed about their waists, it flickered on the ground and made it rosy for their feet, it bloomed upon the ceiling that its glow might set off their bright faces, and it kindled up a general illumination in Mrs. Craggs's little belfry.

Now, too, the lively air that fanned it, grew less gentle as the music quickened and the dance proceeded with new spirit; and a breeze arose that made the leaves and berries dance upon the wall, as they had often done upon the trees; and the breeze rustled in the room as if an invisible company of fairies, treading in the foot-steps of the good substantial revellers, were whirling after them. Now, too, no feature of the Doctor's face could be distinguished as he spun and spun; and now there seemed a dozen Birds of Paradise in fitful flight; and now there were a thousand little bells at work; and now a fleet of flying skirts was ruffled by a little tempest, when the music gave in, and the dance was over.

Hot and breathless as the Doctor was, it only made him the more impatient for Alfred's coming.

'Anything been seen, Britain? Anything been heard?'

'Too dark to see far, sir. Too much noise inside the house to hear.'

'That's right! The gayer welcome for him. How goes the time?'

'Just twelve, sir. He can't be long, sir.'

'Stir up the fire, and throw another log upon it,' said the Doctor. 'Let him see his welcome blazing out upon the night - good boy! - as he comes along!'

He saw it - Yes! From the chaise he caught the light, as he turned the corner by the old church. He knew the room from which it shone. He saw the wintry branches of the old trees between the light and him. He knew that one of those trees rustled musically in the summer time at the window of Marion's chamber.

The tears were in his eyes. His heart throbbed so violently that he could hardly bear his happiness. How often he had thought of this time - pictured it under all circumstances - feared that it might never come - yearned, and wearied for it - far away!

Again the light! Distinct and ruddy; kindled, he knew, to give him welcome, and to speed him home. He beckoned with his hand, and waved his hat, and cheered out, loud, as if the light were they, and they could see and hear him, as he dashed towards them through the mud and mire, triumphantly.

Stop! He knew the Doctor, and understood what he had done. He would not let it be a surprise to them. But he could make it one, yet, by going forward on foot. If the orchard-gate were open, he could enter there; if not, the wall was easily climbed, as he knew of old; and he would be among them in an instant.

He dismounted from the

chaise, and telling the driver - even that was not easy in his agitation - to remain behind for a few minutes, and then to follow slowly, ran on with exceeding swiftness, tried the gate, scaled the wall, jumped down on the other side, and stood panting in the old orchard.

There was a frosty rime upon the trees, which, in the faint light of the clouded moon, hung upon the smaller branches like dead garlands. Withered leaves crackled and snapped beneath his feet, as he crept softly on towards the house. The desolation of a winter night sat brooding on the earth, and in the sky. But, the red light came cheerily towards him from the windows; figures passed and repassed there; and the hum and murmur of voices greeted his ear sweetly.

Listening for hers: attempting, as he crept on, to detach it from the rest, and half believing that he heard it: he had nearly reached the door, when it was abruptly opened, and a figure coming out encountered his. It instantly recoiled with a half-suppressed cry.

'Clemency,' he said, 'don't you know me?'

'Don't come in!' she answered, pushing him back. 'Go away. Don't ask me why. Don't come in.'

'What is the matter?' he exclaimed.

'I don't know. I - I am afraid to think. Go back. Hark!'

There was a sudden tumult in the house. She put her hands upon her ears. A wild scream, such as no hands could shut out, was heard; and Grace - distraction in her looks and manner - rushed out at the door.

'Grace!' He caught her in his arms. 'What is it! Is she dead!'

She disengaged herself, as if to recognise his face, and fell down at his feet.

A crowd of figures came about them from the house. Among them was her father, with a paper in his hand.

'What is it!' cried Alfred, grasping his hair with his hands, and looking in an agony from face to face, as he bent upon his knee beside the insensible girl. 'Will no one look at me? Will no one speak to me? Does no one know me? Is there no voice among you all, to tell me what it is!'

There was a murmur among them. 'She is gone.'

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories