- Home

- Charles Dickens

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Page 6

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Read online

Page 6

CHAPTER VI--PHILANTHROPY IN MINOR CANON CORNER

The Reverend Septimus Crisparkle (Septimus, because six little brotherCrisparkles before him went out, one by one, as they were born, like sixweak little rushlights, as they were lighted), having broken the thinmorning ice near Cloisterham Weir with his amiable head, much to theinvigoration of his frame, was now assisting his circulation by boxing ata looking-glass with great science and prowess. A fresh and healthyportrait the looking-glass presented of the Reverend Septimus, feintingand dodging with the utmost artfulness, and hitting out from the shoulderwith the utmost straightness, while his radiant features teemed withinnocence, and soft-hearted benevolence beamed from his boxing-gloves.

It was scarcely breakfast-time yet, for Mrs. Crisparkle--mother, not wifeof the Reverend Septimus--was only just down, and waiting for the urn.Indeed, the Reverend Septimus left off at this very moment to take thepretty old lady's entering face between his boxing-gloves and kiss it.Having done so with tenderness, the Reverend Septimus turned to again,countering with his left, and putting in his right, in a tremendousmanner.

'I say, every morning of my life, that you'll do it at last, Sept,'remarked the old lady, looking on; 'and so you will.'

'Do what, Ma dear?'

'Break the pier-glass, or burst a blood-vessel.'

'Neither, please God, Ma dear. Here's wind, Ma. Look at this!' In aconcluding round of great severity, the Reverend Septimus administeredand escaped all sorts of punishment, and wound up by getting the oldlady's cap into Chancery--such is the technical term used in scientificcircles by the learned in the Noble Art--with a lightness of touch thathardly stirred the lightest lavender or cherry riband on it.Magnanimously releasing the defeated, just in time to get his gloves intoa drawer and feign to be looking out of window in a contemplative stateof mind when a servant entered, the Reverend Septimus then gave place tothe urn and other preparations for breakfast. These completed, and thetwo alone again, it was pleasant to see (or would have been, if there hadbeen any one to see it, which there never was), the old lady standing tosay the Lord's Prayer aloud, and her son, Minor Canon nevertheless,standing with bent head to hear it, he being within five years of forty:much as he had stood to hear the same words from the same lips when hewas within five months of four.

What is prettier than an old lady--except a young lady--when her eyes arebright, when her figure is trim and compact, when her face is cheerfuland calm, when her dress is as the dress of a china shepherdess: sodainty in its colours, so individually assorted to herself, so neatlymoulded on her? Nothing is prettier, thought the good Minor Canonfrequently, when taking his seat at table opposite his long-widowedmother. Her thought at such times may be condensed into the two wordsthat oftenest did duty together in all her conversations: 'My Sept!'

They were a good pair to sit breakfasting together in Minor Canon Corner,Cloisterham. For Minor Canon Corner was a quiet place in the shadow ofthe Cathedral, which the cawing of the rooks, the echoing footsteps ofrare passers, the sound of the Cathedral bell, or the roll of theCathedral organ, seemed to render more quiet than absolute silence.Swaggering fighting men had had their centuries of ramping and ravingabout Minor Canon Corner, and beaten serfs had had their centuries ofdrudging and dying there, and powerful monks had had their centuries ofbeing sometimes useful and sometimes harmful there, and behold they wereall gone out of Minor Canon Corner, and so much the better. Perhaps oneof the highest uses of their ever having been there, was, that theremight be left behind, that blessed air of tranquillity which pervadedMinor Canon Corner, and that serenely romantic state of themind--productive for the most part of pity and forbearance--which isengendered by a sorrowful story that is all told, or a pathetic play thatis played out.

Red-brick walls harmoniously toned down in colour by time, strong-rootedivy, latticed windows, panelled rooms, big oaken beams in little places,and stone-walled gardens where annual fruit yet ripened upon monkishtrees, were the principal surroundings of pretty old Mrs. Crisparkle andthe Reverend Septimus as they sat at breakfast.

'And what, Ma dear,' inquired the Minor Canon, giving proof of awholesome and vigorous appetite, 'does the letter say?'

The pretty old lady, after reading it, had just laid it down upon thebreakfast-cloth. She handed it over to her son.

Now, the old lady was exceedingly proud of her bright eyes being so clearthat she could read writing without spectacles. Her son was also soproud of the circumstance, and so dutifully bent on her deriving theutmost possible gratification from it, that he had invented the pretencethat he himself could _not_ read writing without spectacles. Thereforehe now assumed a pair, of grave and prodigious proportions, which notonly seriously inconvenienced his nose and his breakfast, but seriouslyimpeded his perusal of the letter. For, he had the eyes of a microscopeand a telescope combined, when they were unassisted.

'It's from Mr. Honeythunder, of course,' said the old lady, folding herarms.

'Of course,' assented her son. He then lamely read on:

'"Haven of Philanthropy, Chief Offices, London, Wednesday.

'"DEAR MADAM,

'"I write in the--;" In the what's this? What does he write in?'

'In the chair,' said the old lady.

The Reverend Septimus took off his spectacles, that he might see herface, as he exclaimed:

'Why, what should he write in?'

'Bless me, bless me, Sept,' returned the old lady, 'you don't see thecontext! Give it back to me, my dear.'

Glad to get his spectacles off (for they always made his eyes water), herson obeyed: murmuring that his sight for reading manuscript got worse andworse daily.

'"I write,"' his mother went on, reading very perspicuously andprecisely, '"from the chair, to which I shall probably be confined forsome hours."'

Septimus looked at the row of chairs against the wall, with ahalf-protesting and half-appealing countenance.

'"We have,"' the old lady read on with a little extra emphasis, '"ameeting of our Convened Chief Composite Committee of Central and DistrictPhilanthropists, at our Head Haven as above; and it is their unanimouspleasure that I take the chair."'

Septimus breathed more freely, and muttered: 'O! if he comes to _that_,let him.'

'"Not to lose a day's post, I take the opportunity of a long report beingread, denouncing a public miscreant--"'

'It is a most extraordinary thing,' interposed the gentle Minor Canon,laying down his knife and fork to rub his ear in a vexed manner, 'thatthese Philanthropists are always denouncing somebody. And it is anothermost extraordinary thing that they are always so violently flush ofmiscreants!'

'"Denouncing a public miscreant--"'--the old lady resumed, '"to get ourlittle affair of business off my mind. I have spoken with my two wards,Neville and Helena Landless, on the subject of their defective education,and they give in to the plan proposed; as I should have taken good carethey did, whether they liked it or not."'

'And it is another most extraordinary thing,' remarked the Minor Canon inthe same tone as before, 'that these philanthropists are so given toseizing their fellow-creatures by the scruff of the neck, and (as one maysay) bumping them into the paths of peace.--I beg your pardon, Ma dear,for interrupting.'

'"Therefore, dear Madam, you will please prepare your son, the Rev. Mr.Septimus, to expect Neville as an inmate to be read with, on Monday next.On the same day Helena will accompany him to Cloisterham, to take up herquarters at the Nuns' House, the establishment recommended by yourselfand son jointly. Please likewise to prepare for her reception andtuition there. The terms in both cases are understood to be exactly asstated to me in writing by yourself, when I opened a correspondence withyou on this subject, after the honour of being introduced to you at yoursister's house in town here. With compliments to the Rev. Mr. Septimus,I am, Dear Madam, Your affectionate brother (In Philanthropy), LUKEHONEYTHUNDER."'

'W

ell, Ma,' said Septimus, after a little more rubbing of his ear, 'wemust try it. There can be no doubt that we have room for an inmate, andthat I have time to bestow upon him, and inclination too. I must confessto feeling rather glad that he is not Mr. Honeythunder himself. Thoughthat seems wretchedly prejudiced--does it not?--for I never saw him. Ishe a large man, Ma?'

'I should call him a large man, my dear,' the old lady replied after somehesitation, 'but that his voice is so much larger.'

'Than himself?'

'Than anybody.'

'Hah!' said Septimus. And finished his breakfast as if the flavour ofthe Superior Family Souchong, and also of the ham and toast and eggs,were a little on the wane.

Mrs. Crisparkle's sister, another piece of Dresden china, and matchingher so neatly that they would have made a delightful pair of ornamentsfor the two ends of any capacious old-fashioned chimneypiece, and byright should never have been seen apart, was the childless wife of aclergyman holding Corporation preferment in London City. Mr.Honeythunder in his public character of Professor of Philanthropy hadcome to know Mrs. Crisparkle during the last re-matching of the chinaornaments (in other words during her last annual visit to her sister),after a public occasion of a philanthropic nature, when certain devotedorphans of tender years had been glutted with plum buns, and plumpbumptiousness. These were all the antecedents known in Minor CanonCorner of the coming pupils.

'I am sure you will agree with me, Ma,' said Mr. Crisparkle, afterthinking the matter over, 'that the first thing to be done, is, to putthese young people as much at their ease as possible. There is nothingdisinterested in the notion, because we cannot be at our ease with themunless they are at their ease with us. Now, Jasper's nephew is down hereat present; and like takes to like, and youth takes to youth. He is acordial young fellow, and we will have him to meet the brother and sisterat dinner. That's three. We can't think of asking him, without askingJasper. That's four. Add Miss Twinkleton and the fairy bride that is tobe, and that's six. Add our two selves, and that's eight. Would eightat a friendly dinner at all put you out, Ma?'

'Nine would, Sept,' returned the old lady, visibly nervous.

'My dear Ma, I particularise eight.'

'The exact size of the table and the room, my dear.'

So it was settled that way: and when Mr. Crisparkle called with hismother upon Miss Twinkleton, to arrange for the reception of Miss HelenaLandless at the Nuns' House, the two other invitations having referenceto that establishment were proffered and accepted. Miss Twinkleton did,indeed, glance at the globes, as regretting that they were not formed tobe taken out into society; but became reconciled to leaving them behind.Instructions were then despatched to the Philanthropist for the departureand arrival, in good time for dinner, of Mr. Neville and Miss Helena; andstock for soup became fragrant in the air of Minor Canon Corner.

In those days there was no railway to Cloisterham, and Mr. Sapsea saidthere never would be. Mr. Sapsea said more; he said there never shouldbe. And yet, marvellous to consider, it has come to pass, in these days,that Express Trains don't think Cloisterham worth stopping at, but yelland whirl through it on their larger errands, casting the dust off theirwheels as a testimony against its insignificance. Some remote fragmentof Main Line to somewhere else, there was, which was going to ruin theMoney Market if it failed, and Church and State if it succeeded, and (ofcourse), the Constitution, whether or no; but even that had already sounsettled Cloisterham traffic, that the traffic, deserting the high road,came sneaking in from an unprecedented part of the country by a backstable-way, for many years labelled at the corner: 'Beware of the Dog.'

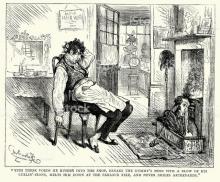

To this ignominious avenue of approach, Mr. Crisparkle repaired, awaitingthe arrival of a short, squat omnibus, with a disproportionate heap ofluggage on the roof--like a little Elephant with infinitely too muchCastle--which was then the daily service between Cloisterham and externalmankind. As this vehicle lumbered up, Mr. Crisparkle could hardly seeanything else of it for a large outside passenger seated on the box, withhis elbows squared, and his hands on his knees, compressing the driverinto a most uncomfortably small compass, and glowering about him with astrongly-marked face.

'Is this Cloisterham?' demanded the passenger, in a tremendous voice.

'It is,' replied the driver, rubbing himself as if he ached, afterthrowing the reins to the ostler. 'And I never was so glad to see it.'

'Tell your master to make his box-seat wider, then,' returned thepassenger. 'Your master is morally bound--and ought to be legally, underruinous penalties--to provide for the comfort of his fellow-man.'

The driver instituted, with the palms of his hands, a superficialperquisition into the state of his skeleton; which seemed to make himanxious.

'Have I sat upon you?' asked the passenger.

'You have,' said the driver, as if he didn't like it at all.

'Take that card, my friend.'

'I think I won't deprive you on it,' returned the driver, casting hiseyes over it with no great favour, without taking it. 'What's the goodof it to me?'

'Be a Member of that Society,' said the passenger.

'What shall I get by it?' asked the driver.

'Brotherhood,' returned the passenger, in a ferocious voice.

'Thankee,' said the driver, very deliberately, as he got down; 'my motherwas contented with myself, and so am I. I don't want no brothers.'

'But you must have them,' replied the passenger, also descending,'whether you like it or not. I am your brother.'

'I say!' expostulated the driver, becoming more chafed in temper, 'nottoo fur! The worm _will_, when--'

But here, Mr. Crisparkle interposed, remonstrating aside, in a friendlyvoice: 'Joe, Joe, Joe! don't forget yourself, Joe, my good fellow!' andthen, when Joe peaceably touched his hat, accosting the passenger with:'Mr. Honeythunder?'

'That is my name, sir.'

'My name is Crisparkle.'

'Reverend Mr. Septimus? Glad to see you, sir. Neville and Helena areinside. Having a little succumbed of late, under the pressure of mypublic labours, I thought I would take a mouthful of fresh air, and comedown with them, and return at night. So you are the Reverend Mr.Septimus, are you?' surveying him on the whole with disappointment, andtwisting a double eyeglass by its ribbon, as if he were roasting it, butnot otherwise using it. 'Hah! I expected to see you older, sir.'

'I hope you will,' was the good-humoured reply.

'Eh?' demanded Mr. Honeythunder.

'Only a poor little joke. Not worth repeating.'

'Joke? Ay; I never see a joke,' Mr. Honeythunder frowningly retorted.'A joke is wasted upon me, sir. Where are they? Helena and Neville,come here! Mr. Crisparkle has come down to meet you.'

An unusually handsome lithe young fellow, and an unusually handsome lithegirl; much alike; both very dark, and very rich in colour; she of almostthe gipsy type; something untamed about them both; a certain air uponthem of hunter and huntress; yet withal a certain air of being theobjects of the chase, rather than the followers. Slender, supple, quickof eye and limb; half shy, half defiant; fierce of look; an indefinablekind of pause coming and going on their whole expression, both of faceand form, which might be equally likened to the pause before a crouch ora bound. The rough mental notes made in the first five minutes by Mr.Crisparkle would have read thus, _verbatim_.

He invited Mr. Honeythunder to dinner, with a troubled mind (for thediscomfiture of the dear old china shepherdess lay heavy on it), and gavehis arm to Helena Landless. Both she and her brother, as they walked alltogether through the ancient streets, took great delight in what hepointed out of the Cathedral and the Monastery ruin, and wondered--so hisnotes ran on--much as if they were beautiful barbaric captives broughtfrom some wild tropical dominion. Mr. Honeythunder walked in the middleof the road, shouldering the natives out of his way, and loudlydeveloping a scheme he had, for making a raid on all the unemployedpersons in the United Kingdom, laying them every one by the heels injail, and forcing them, on p

ain of prompt extermination, to becomephilanthropists.

Mrs. Crisparkle had need of her own share of philanthropy when she beheldthis very large and very loud excrescence on the little party. Alwayssomething in the nature of a Boil upon the face of society, Mr.Honeythunder expanded into an inflammatory Wen in Minor Canon Corner.Though it was not literally true, as was facetiously charged against himby public unbelievers, that he called aloud to his fellow-creatures:'Curse your souls and bodies, come here and be blessed!' still hisphilanthropy was of that gunpowderous sort that the difference between itand animosity was hard to determine. You were to abolish military force,but you were first to bring all commanding officers who had done theirduty, to trial by court-martial for that offence, and shoot them. Youwere to abolish war, but were to make converts by making war upon them,and charging them with loving war as the apple of their eye. You were tohave no capital punishment, but were first to sweep off the face of theearth all legislators, jurists, and judges, who were of the contraryopinion. You were to have universal concord, and were to get it byeliminating all the people who wouldn't, or conscientiously couldn't, beconcordant. You were to love your brother as yourself, but after anindefinite interval of maligning him (very much as if you hated him), andcalling him all manner of names. Above all things, you were to donothing in private, or on your own account. You were to go to theoffices of the Haven of Philanthropy, and put your name down as a Memberand a Professing Philanthropist. Then, you were to pay up yoursubscription, get your card of membership and your riband and medal, andwere evermore to live upon a platform, and evermore to say what Mr.Honeythunder said, and what the Treasurer said, and what thesub-Treasurer said, and what the Committee said, and what thesub-Committee said, and what the Secretary said, and what theVice-Secretary said. And this was usually said in theunanimously-carried resolution under hand and seal, to the effect: 'Thatthis assembled Body of Professing Philanthropists views, with indignantscorn and contempt, not unmixed with utter detestation and loathingabhorrence'--in short, the baseness of all those who do not belong to it,and pledges itself to make as many obnoxious statements as possible aboutthem, without being at all particular as to facts.

The dinner was a most doleful breakdown. The philanthropist deranged thesymmetry of the table, sat himself in the way of the waiting, blocked upthe thoroughfare, and drove Mr. Tope (who assisted the parlour-maid) tothe verge of distraction by passing plates and dishes on, over his ownhead. Nobody could talk to anybody, because he held forth to everybodyat once, as if the company had no individual existence, but were aMeeting. He impounded the Reverend Mr. Septimus, as an officialpersonage to be addressed, or kind of human peg to hang his oratoricalhat on, and fell into the exasperating habit, common among such orators,of impersonating him as a wicked and weak opponent. Thus, he would ask:'And will you, sir, now stultify yourself by telling me'--and so forth,when the innocent man had not opened his lips, nor meant to open them.Or he would say: 'Now see, sir, to what a position you are reduced. Iwill leave you no escape. After exhausting all the resources of fraudand falsehood, during years upon years; after exhibiting a combination ofdastardly meanness with ensanguined daring, such as the world has notoften witnessed; you have now the hypocrisy to bend the knee before themost degraded of mankind, and to sue and whine and howl for mercy!'Whereat the unfortunate Minor Canon would look, in part indignant and inpart perplexed; while his worthy mother sat bridling, with tears in hereyes, and the remainder of the party lapsed into a sort of gelatinousstate, in which there was no flavour or solidity, and very littleresistance.

But the gush of philanthropy that burst forth when the departure of Mr.Honeythunder began to impend, must have been highly gratifying to thefeelings of that distinguished man. His coffee was produced, by thespecial activity of Mr. Tope, a full hour before he wanted it. Mr.Crisparkle sat with his watch in his hand for about the same period, lesthe should overstay his time. The four young people were unanimous inbelieving that the Cathedral clock struck three-quarters, when itactually struck but one. Miss Twinkleton estimated the distance to theomnibus at five-and-twenty minutes' walk, when it was really five. Theaffectionate kindness of the whole circle hustled him into his greatcoat,and shoved him out into the moonlight, as if he were a fugitive traitorwith whom they sympathised, and a troop of horse were at the back door.Mr. Crisparkle and his new charge, who took him to the omnibus, were sofervent in their apprehensions of his catching cold, that they shut himup in it instantly and left him, with still half-an-hour to spare.

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories