- Home

- Charles Dickens

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby Page 9

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby Read online

Page 9

'A hoarse murmur arose from the company; every man touched, first the hilt of his sword, and then the tip of his nose, with appalling significance.

'What a pleasant thing filial piety is to contemplate! If the daughter of the Baron Von Swillenhausen had pleaded a preoccupied heart, or fallen at her father's feet and corned them in salt tears, or only fainted away, and complimented the old gentleman in frantic ejaculations, the odds are a hundred to one but Swillenhausen Castle would have been turned out at window, or rather the baron turned out at window, and the castle demolished. The damsel held her peace, however, when an early messenger bore the request of Von Koeldwethout next morning, and modestly retired to her chamber, from the casement of which she watched the coming of the suitor and his retinue. She was no sooner assured that the horseman with the large moustachios was her proffered husband, than she hastened to her father's presence, and expressed her readiness to sacrifice herself to secure his peace. The venerable baron caught his child to his arms, and shed a wink of joy.

'There was great feasting at the castle, that day. The four-and- twenty Lincoln greens of Von Koeldwethout exchanged vows of eternal friendship with twelve Lincoln greens of Von Swillenhausen, and promised the old baron that they would drink his wine "Till all was blue"—meaning probably until their whole countenances had acquired the same tint as their noses. Everybody slapped everybody else's back, when the time for parting came; and the Baron Von Koeldwethout and his followers rode gaily home.

'For six mortal weeks, the bears and boars had a holiday. The houses of Koeldwethout and Swillenhausen were united; the spears rusted; and the baron's bugle grew hoarse for lack of blowing.

'Those were great times for the four-and-twenty; but, alas! their high and palmy days had taken boots to themselves, and were already walking off.

'"My dear," said the baroness.

'"My love," said the baron.

'"Those coarse, noisy men—"

'"Which, ma'am?" said the baron, starting.

'The baroness pointed, from the window at which they stood, to the courtyard beneath, where the unconscious Lincoln greens were taking a copious stirrup-cup, preparatory to issuing forth after a boar or two.

'"My hunting train, ma'am," said the baron.

'"Disband them, love," murmured the baroness.

'"Disband them!" cried the baron, in amazement.

'"To please me, love," replied the baroness.

'"To please the devil, ma'am," answered the baron.

'Whereupon the baroness uttered a great cry, and swooned away at the baron's feet.

'What could the baron do? He called for the lady's maid, and roared for the doctor; and then, rushing into the yard, kicked the two Lincoln greens who were the most used to it, and cursing the others all round, bade them go—but never mind where. I don't know the German for it, or I would put it delicately that way.

'It is not for me to say by what means, or by what degrees, some wives manage to keep down some husbands as they do, although I may have my private opinion on the subject, and may think that no Member of Parliament ought to be married, inasmuch as three married members out of every four, must vote according to their wives' consciences (if there be such things), and not according to their own. All I need say, just now, is, that the Baroness Von Koeldwethout somehow or other acquired great control over the Baron Von Koeldwethout, and that, little by little, and bit by bit, and day by day, and year by year, the baron got the worst of some disputed question, or was slyly unhorsed from some old hobby; and that by the time he was a fat hearty fellow of forty-eight or thereabouts, he had no feasting, no revelry, no hunting train, and no hunting—nothing in short that he liked, or used to have; and that, although he was as fierce as a lion, and as bold as brass, he was decidedly snubbed and put down, by his own lady, in his own castle of Grogzwig.

'Nor was this the whole extent of the baron's misfortunes. About a year after his nuptials, there came into the world a lusty young baron, in whose honour a great many fireworks were let off, and a great many dozens of wine drunk; but next year there came a young baroness, and next year another young baron, and so on, every year, either a baron or baroness (and one year both together), until the baron found himself the father of a small family of twelve. Upon every one of these anniversaries, the venerable Baroness Von Swillenhausen was nervously sensitive for the well-being of her child the Baroness Von Koeldwethout; and although it was not found that the good lady ever did anything material towards contributing to her child's recovery, still she made it a point of duty to be as nervous as possible at the castle of Grogzwig, and to divide her time between moral observations on the baron's housekeeping, and bewailing the hard lot of her unhappy daughter. And if the Baron of Grogzwig, a little hurt and irritated at this, took heart, and ventured to suggest that his wife was at least no worse off than the wives of other barons, the Baroness Von Swillenhausen begged all persons to take notice, that nobody but she, sympathised with her dear daughter's sufferings; upon which, her relations and friends remarked, that to be sure she did cry a great deal more than her son-in-law, and that if there were a hard-hearted brute alive, it was that Baron of Grogzwig.

'The poor baron bore it all as long as he could, and when he could bear it no longer lost his appetite and his spirits, and sat himself gloomily and dejectedly down. But there were worse troubles yet in store for him, and as they came on, his melancholy and sadness increased. Times changed. He got into debt. The Grogzwig coffers ran low, though the Swillenhausen family had looked upon them as inexhaustible; and just when the baroness was on the point of making a thirteenth addition to the family pedigree, Von Koeldwethout discovered that he had no means of replenishing them.

'"I don't see what is to be done," said the baron. "I think I'll kill myself."

'This was a bright idea. The baron took an old hunting-knife from a cupboard hard by, and having sharpened it on his boot, made what boys call "an offer" at his throat.

'"Hem!" said the baron, stopping short. "Perhaps it's not sharp enough."

'The baron sharpened it again, and made another offer, when his hand was arrested by a loud screaming among the young barons and baronesses, who had a nursery in an upstairs tower with iron bars outside the window, to prevent their tumbling out into the moat.

'"If I had been a bachelor," said the baron sighing, "I might have done it fifty times over, without being interrupted. Hallo! Put a flask of wine and the largest pipe in the little vaulted room behind the hall."

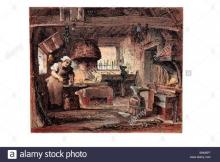

'One of the domestics, in a very kind manner, executed the baron's order in the course of half an hour or so, and Von Koeldwethout being apprised thereof, strode to the vaulted room, the walls of which, being of dark shining wood, gleamed in the light of the blazing logs which were piled upon the hearth. The bottle and pipe were ready, and, upon the whole, the place looked very comfortable.

'"Leave the lamp," said the baron.

'"Anything else, my lord?" inquired the domestic.

'"The room," replied the baron. The domestic obeyed, and the baron locked the door.

'"I'll smoke a last pipe," said the baron, "and then I'll be off." So, putting the knife upon the table till he wanted it, and tossing off a goodly measure of wine, the Lord of Grogzwig threw himself back in his chair, stretched his legs out before the fire, and puffed away.

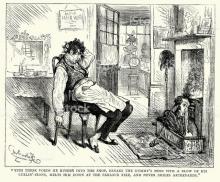

'He thought about a great many things—about his present troubles and past days of bachelorship, and about the Lincoln greens, long since dispersed up and down the country, no one knew whither: with the exception of two who had been unfortunately beheaded, and four who had killed themselves with drinking. His mind was running upon bears and boars, when, in the process of draining his glass to the bottom, he raised his eyes, and saw, for the first time and with unbounded astonishment, that he was not alone.

'No, he was not; for, on the opposite side of the fire, there sat with folded arms a wrinkled hideous figure, with deeply sunk and bloodshot eyes, and an immensely long cadaverous face, shadowed by jagged and

matted locks of coarse black hair. He wore a kind of tunic of a dull bluish colour, which, the baron observed, on regarding it attentively, was clasped or ornamented down the front with coffin handles. His legs, too, were encased in coffin plates as though in armour; and over his left shoulder he wore a short dusky cloak, which seemed made of a remnant of some pall. He took no notice of the baron, but was intently eyeing the fire.

'"Halloa!" said the baron, stamping his foot to attract attention.

'"Halloa!" replied the stranger, moving his eyes towards the baron, but not his face or himself "What now?"

'"What now!" replied the baron, nothing daunted by his hollow voice and lustreless eyes. "I should ask that question. How did you get here?"

'"Through the door," replied the figure.

'"What are you?" says the baron.

'"A man," replied the figure.

'"I don't believe it," says the baron.

'"Disbelieve it then," says the figure.

'"I will," rejoined the baron.

'The figure looked at the bold Baron of Grogzwig for some time, and then said familiarly,

'"There's no coming over you, I see. I'm not a man!"

'"What are you then?" asked the baron.

'"A genius," replied the figure.

'"You don't look much like one," returned the baron scornfully.

'"I am the Genius of Despair and Suicide," said the apparition. "Now you know me."

'With these words the apparition turned towards the baron, as if composing himself for a talk—and, what was very remarkable, was, that he threw his cloak aside, and displaying a stake, which was run through the centre of his body, pulled it out with a jerk, and laid it on the table, as composedly as if it had been a walking-stick.

'"Now," said the figure, glancing at the hunting-knife, "are you ready for me?"

'"Not quite," rejoined the baron; "I must finish this pipe first."

'"Look sharp then," said the figure.

'"You seem in a hurry," said the baron.

'"Why, yes, I am," answered the figure; "they're doing a pretty brisk business in my way, over in England and France just now, and my time is a good deal taken up."

'"Do you drink?" said the baron, touching the bottle with the bowl of his pipe.

'"Nine times out of ten, and then very hard," rejoined the figure, drily.

'"Never in moderation?" asked the baron.

'"Never," replied the figure, with a shudder, "that breeds cheerfulness."

'The baron took another look at his new friend, whom he thought an uncommonly queer customer, and at length inquired whether he took any active part in such little proceedings as that which he had in contemplation.

'"No," replied the figure evasively; "but I am always present."

'"Just to see fair, I suppose?" said the baron.

'"Just that," replied the figure, playing with his stake, and examining the ferule. "Be as quick as you can, will you, for there's a young gentleman who is afflicted with too much money and leisure wanting me now, I find."

'"Going to kill himself because he has too much money!" exclaimed the baron, quite tickled. "Ha! ha! that's a good one." (This was the first time the baron had laughed for many a long day.)

'"I say," expostulated the figure, looking very much scared; "don't do that again."

'"Why not?" demanded the baron.

'"Because it gives me pain all over," replied the figure. "Sigh as much as you please: that does me good."

'The baron sighed mechanically at the mention of the word; the figure, brightening up again, handed him the hunting-knife with most winning politeness.

'"It's not a bad idea though," said the baron, feeling the edge of the weapon; "a man killing himself because he has too much money."

'"Pooh!" said the apparition, petulantly, "no better than a man's killing himself because he has none or little."

'Whether the genius unintentionally committed himself in saying this, or whether he thought the baron's mind was so thoroughly made up that it didn't matter what he said, I have no means of knowing. I only know that the baron stopped his hand, all of a sudden, opened his eyes wide, and looked as if quite a new light had come upon him for the first time.

'"Why, certainly," said Von Koeldwethout, "nothing is too bad to be retrieved."

'"Except empty coffers," cried the genius.

'"Well; but they may be one day filled again," said the baron.

'"Scolding wives," snarled the genius.

'"Oh! They may be made quiet," said the baron.

'"Thirteen children," shouted the genius.

'"Can't all go wrong, surely," said the baron.

'The genius was evidently growing very savage with the baron, for holding these opinions all at once; but he tried to laugh it off, and said if he would let him know when he had left off joking he should feel obliged to him.

'"But I am not joking; I was never farther from it," remonstrated the baron.

'"Well, I am glad to hear that," said the genius, looking very grim, "because a joke, without any figure of speech, IS the death of me. Come! Quit this dreary world at once."

'"I don't know," said the baron, playing with the knife; "it's a dreary one certainly, but I don't think yours is much better, for you have not the appearance of being particularly comfortable. That puts me in mind—what security have I, that I shall be any the better for going out of the world after all!" he cried, starting up; "I never thought of that."

'"Dispatch," cried the figure, gnashing his teeth.

'"Keep off!" said the baron. 'I'll brood over miseries no longer, but put a good face on the matter, and try the fresh air and the bears again; and if that don't do, I'll talk to the baroness soundly, and cut the Von Swillenhausens dead.' With this the baron fell into his chair, and laughed so loud and boisterously, that the room rang with it.

'The figure fell back a pace or two, regarding the baron meanwhile with a look of intense terror, and when he had ceased, caught up the stake, plunged it violently into its body, uttered a frightful howl, and disappeared.

'Von Koeldwethout never saw it again. Having once made up his mind to action, he soon brought the baroness and the Von Swillenhausens to reason, and died many years afterwards: not a rich man that I am aware of, but certainly a happy one: leaving behind him a numerous family, who had been carefully educated in bear and boar-hunting under his own personal eye. And my advice to all men is, that if ever they become hipped and melancholy from similar causes (as very many men do), they look at both sides of the question, applying a magnifying-glass to the best one; and if they still feel tempted to retire without leave, that they smoke a large pipe and drink a full bottle first, and profit by the laudable example of the Baron of Grogzwig.'

'The fresh coach is ready, ladies and gentlemen, if you please,' said a new driver, looking in.

This intelligence caused the punch to be finished in a great hurry, and prevented any discussion relative to the last story. Mr Squeers was observed to draw the grey-headed gentleman on one side, and to ask a question with great apparent interest; it bore reference to the Five Sisters of York, and was, in fact, an inquiry whether he could inform him how much per annum the Yorkshire convents got in those days with their boarders.

The journey was then resumed. Nicholas fell asleep towards morning, and, when he awoke, found, with great regret, that, during his nap, both the Baron of Grogzwig and the grey-haired gentleman had got down and were gone. The day dragged on uncomfortably enough. At about six o'clock that night, he and Mr Squeers, and the little boys, and their united luggage, were all put down together at the George and New Inn, Greta Bridge.

Chapter 7

Mr and Mrs Squeers at Home

Mr Squeers, being safely landed, left Nicholas and the boys standing with the luggage in the road, to amuse themselves by looking at the coach as it changed horses, while he ran into the tavern and went through the leg-stretching process at the bar. After some minutes, he returned, with his legs thorou

ghly stretched, if the hue of his nose and a short hiccup afforded any criterion; and at the same time there came out of the yard a rusty pony-chaise, and a cart, driven by two labouring men.

'Put the boys and the boxes into the cart,' said Squeers, rubbing his hands; 'and this young man and me will go on in the chaise. Get in, Nickleby.'

Nicholas obeyed. Mr. Squeers with some difficulty inducing the pony to obey also, they started off, leaving the cart-load of infant misery to follow at leisure.

'Are you cold, Nickleby?' inquired Squeers, after they had travelled some distance in silence.

'Rather, sir, I must say.'

'Well, I don't find fault with that,' said Squeers; 'it's a long journey this weather.'

'Is it much farther to Dotheboys Hall, sir?' asked Nicholas.

'About three mile from here,' replied Squeers. 'But you needn't call it a Hall down here.'

Nicholas coughed, as if he would like to know why.

'The fact is, it ain't a Hall,' observed Squeers drily.

'Oh, indeed!' said Nicholas, whom this piece of intelligence much astonished.

'No,' replied Squeers. 'We call it a Hall up in London, because it sounds better, but they don't know it by that name in these parts. A man may call his house an island if he likes; there's no act of Parliament against that, I believe?'

'I believe not, sir,' rejoined Nicholas.

Squeers eyed his companion slyly, at the conclusion of this little dialogue, and finding that he had grown thoughtful and appeared in nowise disposed to volunteer any observations, contented himself with lashing the pony until they reached their journey's end.

'Jump out,' said Squeers. 'Hallo there! Come and put this horse up. Be quick, will you!'

While the schoolmaster was uttering these and other impatient cries, Nicholas had time to observe that the school was a long, cold- looking house, one storey high, with a few straggling out-buildings behind, and a barn and stable adjoining. After the lapse of a minute or two, the noise of somebody unlocking the yard-gate was heard, and presently a tall lean boy, with a lantern in his hand, issued forth.

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

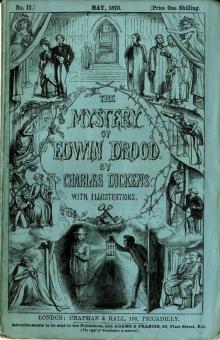

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

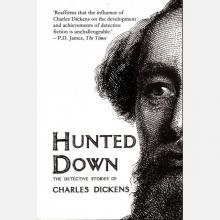

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

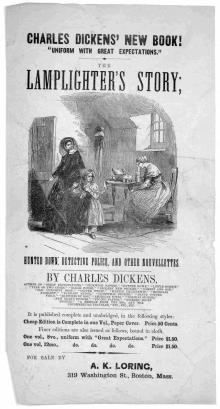

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories