- Home

- Charles Dickens

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 Page 9

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 Read online

Page 9

‘The marriage that takes place to–day,’ said Caleb, ‘is with a stern, sordid, grinding man. A hard master to you and me, my dear, for many years. Ugly in his looks, and in his nature. Cold and callous always. Unlike what I have painted him to you in everything, my child. In everything.’

‘Oh why,’ cried the Blind Girl, tortured, as it seemed, almost beyond endurance, ‘why did you ever do this! Why did you ever fill my heart so full, and then come in like Death, and tear away the objects of my love! O Heaven, how blind I am! How helpless and alone!’

Her afflicted father hung his head, and offered no reply but in his penitence and sorrow.

She had been but a short time in this passion of regret, when the Cricket on the Hearth, unheard by all but her, began to chirp. Not merrily, but in a low, faint, sorrowing way. It was so mournful that her tears began to flow; and when the Presence which had been beside the Carrier all night, appeared behind her, pointing to her father, they fell down like rain.

She heard the Cricket–voice more plainly soon, and was conscious, through her blindness, of the Presence hovering about her father.

‘Mary,’ said the Blind Girl, ‘tell me what my home is. What it truly is.’

‘It is a poor place, Bertha; very poor and bare indeed. The house will scarcely keep out wind and rain another winter. It is as roughly shielded from the weather, Bertha,’ Dot continued in a low, clear voice, ‘as your poor father in his sack–cloth coat.’

The Blind Girl, greatly agitated, rose, and led the Carrier’s little wife aside.

‘Those presents that I took such care of; that came almost at my wish, and were so dearly welcome to me,’ she said, trembling; ‘where did they come from? Did you send them?’

‘No.’

‘Who then?’

Dot saw she knew, already, and was silent. The Blind Girl spread her hands before her face again. But in quite another manner now.

‘Dear Mary, a moment. One moment? More this way. Speak softly to me. You are true, I know. You’d not deceive me now; would you?’

‘No, Bertha, indeed!’

‘No, I am sure you would not. You have too much pity for me. Mary, look across the room to where we were just now—to where my father is—my father, so compassionate and loving to me—and tell me what you see.’

‘I see,’ said Dot, who understood her well, ‘an old man sitting in a chair, and leaning sorrowfully on the back, with his face resting on his hand. As if his child should comfort him, Bertha.’

‘Yes, yes. She will. Go on.’

‘He is an old man, worn with care and work. He is a spare, dejected, thoughtful, grey–haired man. I see him now, despondent and bowed down, and striving against nothing. But, Bertha, I have seen him many times before, and striving hard in many ways for one great sacred object. And I honour his grey head, and bless him!’

The Blind Girl broke away from her; and throwing herself upon her knees before him, took the grey head to her breast.

‘It is my sight restored. It is my sight!’ she cried. ‘I have been blind, and now my eyes are open. I never knew him! To think I might have died, and never truly seen the father who has been so loving to me!’

There were no words for Caleb’s emotion.

‘There is not a gallant figure on this earth,’ exclaimed the Blind Girl, holding him in her embrace, ‘that I would love so dearly, and would cherish so devotedly, as this! The greyer, and more worn, the dearer, father! Never let them say I am blind again. There’s not a furrow in his face, there’s not a hair upon his head, that shall be forgotten in my prayers and thanks to Heaven!’

Caleb managed to articulate ‘My Bertha!’

‘And in my blindness, I believed him,’ said the girl, caressing him with tears of exquisite affection, ‘to be so different! And having him beside me, day by day, so mindful of me—always, never dreamed of this!’

‘The fresh smart father in the blue coat, Bertha,’ said poor Caleb. ‘He’s gone!’

‘Nothing is gone,’ she answered. ‘Dearest father, no! Everything is here—in you. The father that I loved so well; the father that I never loved enough, and never knew; the benefactor whom I first began to reverence and love, because he had such sympathy for me; All are here in you. Nothing is dead to me. The soul of all that was most dear to me is here—here, with the worn face, and the grey head. And I am not blind, father, any longer!’

Dot’s whole attention had been concentrated, during this discourse, upon the father and daughter; but looking, now, towards the little Haymaker in the Moorish meadow, she saw that the clock was within a few minutes of striking, and fell, immediately, into a nervous and excited state.

‘Father,’ said Bertha, hesitating. ‘Mary.’

‘Yes, my dear,’ returned Caleb. ‘Here she is.’

‘There is no change in her. You never told me anything of her that was not true?’

‘I should have done it, my dear, I am afraid,’ returned Caleb, ‘if I could have made her better than she was. But I must have changed her for the worse, if I had changed her at all. Nothing could improve her, Bertha.’

Confident as the Blind Girl had been when she asked the question, her delight and pride in the reply and her renewed embrace of Dot, were charming to behold.

‘More changes than you think for, may happen though, my dear,’ said Dot. ‘Changes for the better, I mean; changes for great joy to some of us. You mustn’t let them startle you too much, if any such should ever happen, and affect you? Are those wheels upon the road? You’ve a quick ear, Bertha. Are they wheels?’

‘Yes. Coming very fast.’

‘I—I—I know you have a quick ear,’ said Dot, placing her hand upon her heart, and evidently talking on, as fast as she could to hide its palpitating state, ‘because I have noticed it often, and because you were so quick to find out that strange step last night. Though why you should have said, as I very well recollect you did say, Bertha, “Whose step is that!” and why you should have taken any greater observation of it than of any other step, I don’t know. Though as I said just now, there are great changes in the world: great changes: and we can’t do better than prepare ourselves to be surprised at hardly anything.’

Caleb wondered what this meant; perceiving that she spoke to him, no less than to his daughter. He saw her, with astonishment, so fluttered and distressed that she could scarcely breathe; and holding to a chair, to save herself from falling.

‘They are wheels indeed!’ she panted. ‘Coming nearer! Nearer! Very close! And now you hear them stopping at the garden–gate! And now you hear a step outside the door—the same step, Bertha, is it not!—and now!’—

She uttered a wild cry of uncontrollable delight; and running up to Caleb put her hands upon his eyes, as a young man rushed into the room, and flinging away his hat into the air, came sweeping down upon them.

‘Is it over?’ cried Dot.

‘Yes!’

‘Happily over?’

‘Yes!’

‘Do you recollect the voice, dear Caleb? Did you ever hear the like of it before?’ cried Dot.

‘If my boy in the Golden South Americas was alive’—said Caleb, trembling.

‘He is alive!’ shrieked Dot, removing her hands from his eyes, and clapping them in ecstasy; ‘look at him! See where he stands before you, healthy and strong! Your own dear son! Your own dear living, loving brother, Bertha

All honour to the little creature for her transports! All honour to her tears and laughter, when the three were locked in one another’s arms! All honour to the heartiness with which she met the sunburnt sailor–fellow, with his dark streaming hair, half–way, and never turned her rosy little mouth aside, but suffered him to kiss it, freely, and to press her to his bounding heart!

And honour to the Cuckoo too—why not!—for bursting out of the trap–door in the Moorish Palace like a house–breaker, and hiccoughing twelve times on the assembled company, as if he had got drunk for joy!

The Carrier, ent

ering, started back. And well he might, to find himself in such good company.

‘Look, John!’ said Caleb, exultingly, ‘look here! My own boy from the Golden South Americas! My own son! Him that you fitted out, and sent away yourself! Him that you were always such a friend to!’

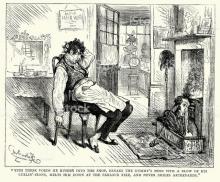

The Carrier advanced to seize him by the hand; but, recoiling, as some feature in his face awakened a remembrance of the Deaf Man in the Cart, said:

‘Edward! Was it you?’

‘Now tell him all!’ cried Dot. ‘Tell him all, Edward; and don’t spare me, for nothing shall make me spare myself in his eyes, ever again.’

‘I was the man,’ said Edward.

‘And could you steal, disguised, into the house of your old friend?’ rejoined the Carrier. ‘There was a frank boy once—how many years is it, Caleb, since we heard that he was dead, and had it proved, we thought?—who never would have done that.’

‘There was a generous friend of mine, once; more a father to me than a friend;’ said Edward, ‘who never would have judged me, or any other man, unheard. You were he. So I am certain you will hear me now.’

The Carrier, with a troubled glance at Dot, who still kept far away from him, replied, ‘Well! that’s but fair. I will.’

‘You must know that when I left here, a boy,’ said Edward, ‘I was in love, and my love was returned. She was a very young girl, who perhaps (you may tell me) didn’t know her own mind. But I knew mine, and I had a passion for her.’

‘You had!’ exclaimed the Carrier. ‘You!’

‘Indeed I had,’ returned the other. ‘And she returned it. I have ever since believed she did, and now I am sure she did.’

‘Heaven help me!’ said the Carrier. ‘This is worse than all.’

‘Constant to her,’ said Edward, ‘and returning, full of hope, after many hardships and perils, to redeem my part of our old contract, I heard, twenty miles away, that she was false to me; that she had forgotten me; and had bestowed herself upon another and a richer man. I had no mind to reproach her; but I wished to see her, and to prove beyond dispute that this was true. I hoped she might have been forced into it, against her own desire and recollection. It would be small comfort, but it would be some, I thought, and on I came. That I might have the truth, the real truth; observing freely for myself, and judging for myself, without obstruction on the one hand, or presenting my own influence (if I had any) before her, on the other; I dressed myself unlike myself—you know how; and waited on the road—you know where. You had no suspicion of me; neither had—had she,’ pointing to Dot, ‘until I whispered in her ear at that fireside, and she so nearly betrayed me.’

‘But when she knew that Edward was alive, and had come back,’ sobbed Dot, now speaking for herself, as she had burned to do, all through this narrative; ‘and when she knew his purpose, she advised him by all means to keep his secret close; for his old friend John Peerybingle was much too open in his nature, and too clumsy in all artifice—being a clumsy man in general,’ said Dot, half laughing and half crying—‘to keep it for him. And when she—that’s me, John,’ sobbed the little woman—‘told him all, and how his sweetheart had believed him to be dead; and how she had at last been over–persuaded by her mother into a marriage which the silly, dear old thing called advantageous; and when she—that’s me again, John—told him they were not yet married (though close upon it), and that it would be nothing but a sacrifice if it went on, for there was no love on her side; and when he went nearly mad with joy to hear it; then she—that’s me again—said she would go between them, as she had often done before in old times, John, and would sound his sweetheart and be sure that what she—me again, John—said and thought was right. And it was right, John! And they were brought together, John! And they were married, John, an hour ago! And here’s the Bride! And Gruff and Tackleton may die a bachelor! And I’m a happy little woman, May, God bless you!’

She was an irresistible little woman, if that be anything to the purpose; and never so completely irresistible as in her present transports. There never were congratulations so endearing and delicious, as those she lavished on herself and on the Bride.

Amid the tumult of emotions in his breast, the honest Carrier had stood, confounded. Flying, now, towards her, Dot stretched out her hand to stop him, and retreated as before.

‘No, John, no! Hear all! Don’t love me any more, John, till you’ve heard every word I have to say. It was wrong to have a secret from you, John. I’m very sorry. I didn’t think it any harm, till I came and sat down by you on the little stool last night. But when I knew by what was written in your face, that you had seen me walking in the gallery with Edward, and when I knew what you thought, I felt how giddy and how wrong it was. But oh, dear John, how could you, could you, think so!’

Little woman, how she sobbed again! John Peerybingle would have caught her in his arms. But no; she wouldn’t let him.

‘Don’t love me yet, please, John! Not for a long time yet! When I was sad about this intended marriage, dear, it was because I remembered May and Edward such young lovers; and knew that her heart was far away from Tackleton. You believe that, now. Don’t you, John?’

John was going to make another rush at this appeal; but she stopped him again.

‘No; keep there, please, John! When I laugh at you, as I sometimes do, John, and call you clumsy and a dear old goose, and names of that sort, it’s because I love you, John, so well, and take such pleasure in your ways, and wouldn’t see you altered in the least respect to have you made a King to–morrow.’

‘Hooroar!’ said Caleb with unusual vigour. ‘My opinion!’

‘And when I speak of people being middle–aged, and steady, John, and pretend that we are a humdrum couple, going on in a jog–trot sort of way, it’s only because I’m such a silly little thing, John, that I like, sometimes, to act a kind of Play with Baby, and all that: and make believe.’

She saw that he was coming; and stopped him again. But she was very nearly too late.

‘No, don’t love me for another minute or two, if you please, John! What I want most to tell you, I have kept to the last. My dear, good, generous John, when we were talking the other night about the Cricket, I had it on my lips to say, that at first I did not love you quite so dearly as I do now; that when I first came home here, I was half afraid I mightn’t learn to love you every bit as well as I hoped and prayed I might—being so very young, John! But, dear John, every day and hour I loved you more and more. And if I could have loved you better than I do, the noble words I heard you say this morning, would have made me. But I can’t. All the affection that I had (it was a great deal, John) I gave you, as you well deserve, long, long ago, and I have no more left to give. Now, my dear husband, take me to your heart again! That’s my home, John; and never, never think of sending me to any other!’

You never will derive so much delight from seeing a glorious little woman in the arms of a third party, as you would have felt if you had seen Dot run into the Carrier’s embrace. It was the most complete, unmitigated, soul–fraught little piece of earnestness that ever you beheld in all your days.

You maybe sure the Carrier was in a state of perfect rapture; and you may be sure Dot was likewise; and you may be sure they all were, inclusive of Miss Slowboy, who wept copiously for joy, and wishing to include her young charge in the general interchange of congratulations, handed round the Baby to everybody in succession, as if it were something to drink.

But, now, the sound of wheels was heard again outside the door; and somebody exclaimed that Gruff and Tackleton was coming back. Speedily that worthy gentleman appeared, looking warm and flustered.

‘Why, what the Devil’s this, John Peerybingle!’ said Tackleton. ‘There’s some mistake. I appointed Mrs. Tackleton to meet me at the church, and I’ll swear I passed her on the road, on her way here. Oh! here she is! I beg your pardon, sir; I haven’t the pleasure of knowing you; but if you can do me the favour to spare this young lady, she has rather a particular engage

ment this morning.’

‘But I can’t spare her,’ returned Edward. ‘I couldn’t think of it.’

‘What do you mean, you vagabond?’ said Tackleton.

‘I mean, that as I can make allowance for your being vexed,’ returned the other, with a smile, ‘I am as deaf to harsh discourse this morning, as I was to all discourse last night.’

The look that Tackleton bestowed upon him, and the start he gave!

‘I am sorry, sir,’ said Edward, holding out May’s left hand, and especially the third finger; ‘that the young lady can’t accompany you to church; but as she has been there once, this morning, perhaps you’ll excuse her.’

Tackleton looked hard at the third finger, and took a little piece of silver–paper, apparently containing a ring, from his waistcoat–pocket.

‘Miss Slowboy,’ said Tackleton. ‘Will you have the kindness to throw that in the fire? Thank’ee.’

‘It was a previous engagement, quite an old engagement, that prevented my wife from keeping her appointment with you, I assure you,’ said Edward.

‘Mr. Tackleton will do me the justice to acknowledge that I revealed it to him faithfully; and that I told him, many times, I never could forget it,’ said May, blushing.

‘Oh certainly!’ said Tackleton. ‘Oh to be sure. Oh it’s all right. It’s quite correct. Mrs. Edward Plummer, I infer?’

‘That’s the name,’ returned the bridegroom.

‘Ah, I shouldn’t have known you, sir,’ said Tackleton, scrutinising his face narrowly, and making a low bow. ‘I give you joy, sir!’

‘Thank’ee.’

‘Mrs. Peerybingle,’ said Tackleton, turning suddenly to where she stood with her husband; ‘I am sorry. You haven’t done me a very great kindness, but, upon my life I am sorry. You are better than I thought you. John Peerybingle, I am sorry. You understand me; that’s enough. It’s quite correct, ladies and gentlemen all, and perfectly satisfactory. Good morning!’

With these words he carried it off, and carried himself off too: merely stopping at the door, to take the flowers and favours from his horse’s head, and to kick that animal once, in the ribs, as a means of informing him that there was a screw loose in his arrangements.

Our Mutual Friend

Our Mutual Friend_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 1 (of 2) Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities The Magic Fishbone

The Magic Fishbone Great Expectations

Great Expectations Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read

Dickens' Stories About Children Every Child Can Read A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol Master Humphrey's Clock

Master Humphrey's Clock Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist A Chrismas Carol

A Chrismas Carol David Copperfield

David Copperfield Charles Dickens' Children Stories

Charles Dickens' Children Stories The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens

Hunted Down: The Detective Stories of Charles Dickens The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter Martin Chuzzlewit

Martin Chuzzlewit_preview.jpg) The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2)

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, v. 2 (of 2) Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy

Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master

Captain Boldheart & the Latin-Grammar Master Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings

Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings Stories from Dickens

Stories from Dickens The Mudfog Papers

The Mudfog Papers Bardell v. Pickwick

Bardell v. Pickwick Dickens' Christmas Spirits

Dickens' Christmas Spirits A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth

A Christmas Carol, the Chimes & the Cricket on the Hearth Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son Hunted down

Hunted down The Battle of Life

The Battle of Life A House to Let

A House to Let Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi)

Works of Charles Dickens (200+ Works) The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, David Copperfield & more (mobi) The Adventures of Oliver Twist

The Adventures of Oliver Twist The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™

The Charles Dickens Christmas MEGAPACK™ The Holly Tree

The Holly Tree The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain

The Haunted Man and the Ghost`s Bargain Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit

Life And Adventures Of Martin Chuzzlewit A Message From the Sea

A Message From the Sea Holiday Romance

Holiday Romance Mugby Junction and Other Stories

Mugby Junction and Other Stories Sunday Under Three Heads

Sunday Under Three Heads The Wreck of the Golden Mary

The Wreck of the Golden Mary Sketches by Boz

Sketches by Boz Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics)

Dickens at Christmas (Vintage Classics) All The Year Round

All The Year Round Short Stories

Short Stories Speeches: Literary & Social

Speeches: Literary & Social The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby

The Life And Adventures Of Nicholas Nickleby A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club)

A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations (Oprah's Book Club) Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty

Barnaby Rudge — A Tale Of The Riots Of Eighty Some Christmas Stories

Some Christmas Stories The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5

The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain tc-5 The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack

The Charles Dickens Christmas Megapack The Chimes

The Chimes Mudfog And Other Sketches

Mudfog And Other Sketches Miscellaneous Papers

Miscellaneous Papers Scrooge #worstgiftever

Scrooge #worstgiftever The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales

The Victorian Mystery Megapack: 27 Classic Mystery Tales Selected Short Fiction

Selected Short Fiction George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation The Cricket on the Hearth c-3

The Cricket on the Hearth c-3 The Seven Poor Travellers

The Seven Poor Travellers Doctor Marigold

Doctor Marigold Three Ghost Stories

Three Ghost Stories